Meet Muhammad Abbas Hijazi.

An abstract artist who was showing his work at the First Qur’an Festival.

Comments Off on Day 13 – Hijazi4u – Abstract Qur’an Artist

Meet Muhammad Abbas Hijazi.

An abstract artist who was showing his work at the First Qur’an Festival.

Category:

Share it:

Comments Off on Day 12 – Jame Abu Bakr – Scarborough Muslim Association

On the second Friday of Ramadan, I spent 23 hours at Jame Abu Bakr / Scarborough Muslim Association.

I came for the second Juma Prayers, and stayed until a Janaza Funeral Prayer was said for a elder Muslim sister who had passed away.

InshAllah I’ll update this blog post in depth time permitting.

For now, here are unedited photos during those 23 hours.

Category:

Share it:

Comments Off on 30Mosques.com | Day 22: Understanding Love

By Bassam Tariq

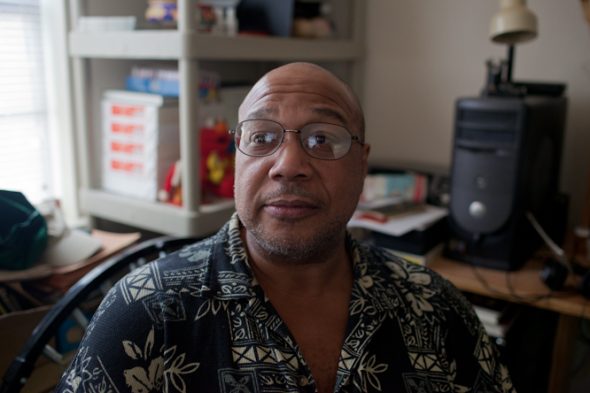

We met a gay Imam yesterday in Washington DC. Before we go any further I thought I’d take a moment and do a Frequently Asked Questions section so we can get passed the obvious questions and move to the story.

WHAT’S THE STORY?

He goes by Imam Daiyee Abdullah and lives in Washington D.C. He is known as the gay Imam because many queer Muslims come to him for advice on how to live a balanced and spiritual life. He is a large man that towered over both Aman and I. He also has a mean handshake.

WHERE’S THE MOSQUE?

For now, it is a makeshift mosque. They meet at a public library in Washington DC for Friday prayers.

HOW DID HE KNOW HE WAS GAY?

Imam Daiyee grew up in a very loving family and always knew that he was gay. He finally came out to his parents when he left for college at the age of 15. At the time, his name was Sidney and he wasn’t Muslim. His family had always instilled in him the importance of believing in God. They themselves are Southern Baptists, but accepted their son when he came out.

HOW DID HE FIND ISLAM?

Oddly enough, in China. He was studying the Chinese language at Beijing University in the early 80’s when he befriend many Uyghur Muslims. He was very moved by the faith. The first Quran he ever read was in Chinese and Arabic. He had been exposed to Islam before with the small Wahhabi and Nation of Islam communities he ran into during college. At that time, the religion didn’t make much sense to him. Ironically, it was when he read the Quran in Chinese that it all came together.

WAIT, WAS HE STILL GAY WHEN HE EMBRACED ISLAM?

Yes. Imam Daiyee has always been a spiritual man and believed in the importance of having faith. What attracted him into Islam was prayer. “With Islam, it’s totally different. In sujood [prostration], I felt like I could release all my anxieties to Allah.” He also feels that the faith gives him a greater inner peace that no other religion has given him.

HOW DID HE RECONCILE ISLAM’S VIEW ON HOMOSEXUALITY AND HIS OWN PRACTICE?

This is where it gets interesting. Imam Daiyee Abdullah was introduced to Islam by the Uyghurs. Apparently, they have been Muslim for over 1300 years because of their tradings with the Arabs. In Imam Daiyee’s eyes they have a wider and more nuanced understanding of Islam and one that is closer to the Prophet’s time. They were very accepting of his homosexuality and embraced him wholeheartedly.

From the moment he was Muslim, Imam Daiyee never saw a conflict between with Islam and homosexuality.

OKAY GOT IT – WHY DOES 30 MOSQUES CARE?

Great question. We are looking to share compelling and relevant stories about Muslims in America. We have celebrated those in the mainstream Muslim community and have also highlighted communities that would be considered on “the fringe.” It was important for us to meet someone from the Queer Muslim community because they exist and their story is an important one. Do I necessarily have to agree with their beliefs and values? No, but I should respect it.

There are countless stories that we have covered this year on communities or people we wouldn’t see eye-to-eye with and that’s what this year’s challenge has been for us. It is for us to step into these difficult conversations and to try to empathize and understand where the other is coming from. That’s the only way we can celebrate the human experience and climb out of our own ignorance.

ARE THERE MANY QUEER MUSLIMS IN AMERICA?

There is no real way to know how many Muslims in the US are queer, but Imam Daiyee estimates about 6%. In his own informal observations, he says that they tend to be well-educated, in their mid to late twenties. They come from all over the world, there is no one real ethnic majority in the congregation.

WHY IS THIS RELEVANT?

We are afraid as a community to touch this subject because we feel the religion doesn’t accept it as a lifestyle. Many muslims right now see homosexuality as a phenomena that doesn’t effect Muslims. We take the Ahmedenejad “there are no homosexuals in Iran.” But what will we do if one of our siblings comes out? If our child tells us they are gay? Or a close friend? Will you still love them? Will you shun them? Beat them?

——

Imam Daiyee has had a few partners in his life. His first long-term committed relationship was when he moved to San Francisco. He is now on his third relationship and for the first time, the person he is seeing is Muslim.

“Every man I’ve dealt with has had children.” He says with a belly laugh.

Many of Imam Diayee’s relationships have been with men that used to be married and have children. His last partner and him were together for 11 years and after they broke up, his partner remarried.

“He remarried?” I ask, puzzled. “to a woman?”

“Yes.” Imam Daiyee replies. “A little while into our relationship he told me that he missed being with a women. I told him ‘that’s fine, but you cant be with the both of us.”

His ex-partner, we’ll call him Ted, wanted both. Imam Daiyee felt that wouldn’t be right. He believed in a committed relationship and believed that there needs to be a standard and a limit to how they have their relationship. Ted didn’t get it.

This entire conversation happens as Aman and I are dropping off Imam Daiyee at his home in DC. We are on our way from having dinner together. This conversation makes me uneasy. It is odd for me to see an Imam, or some kind of Muslim leader talk about his gay boyfriends. It’s hard to accept that Imam Daiyee and I see the world differently because of how our sexual orientation molds our perspective.

It has to be said, there are limits to my understanding of the queer experience because I have never been in a romantic relationship with another man nor have I yearned for that. I am part of the heterosexual norm. But now, Imam Daiyee and I have come together because of our belief in the same God and our upholding of a high moral and ethical standard.

“Is it hard to be in a relationship with someone that’s not Muslim?” I ask since Ted was a Christian.

“Yes, the value systems are different. I’m always explaining myself.”

After the relationship with Ted, Imam Daiyee was in a hiatus for about three years. He is now dating again and, for the first time, he’s a Muslim.

“He also has kids, he’s divorced.” Imam Daiyee says, “I guess I’m here to soften’em up.”

Imam Daiyee laughs again and we all join in. He is a man of great humor and ease. The questions I’ve asked him throughout the day have been very pointed and difficult, but he answers them with grace and respect. He is a patient man that is in no hurry. In answering questions, he takes his time and gives his answers with care.

“We are in a mutah [temporary marriage] relationship right now.” Imam Daiyee says.

He is excited about the future with his Muslim boyfriend. For the first time Imam Daiyee has someone he can fast with, someone he can pray with and someone that he sees eye-to-eye with in terms of morality and standards of what to expect in a relationship.

For his Indian Muslim partner, let’s call him Mubashir, this is his first relationship. Mubashir is also based in DC and had some difficulties in the beginning.

“He started acting really feminine and I told him that I don’t want that. If I want a woman, I could get one.”

Imam Daiyee dated a woman in high school and it didn’t seem to do anything for him. He calls it the time he was in “follow-everyone-else mode.”

Affected behavior is a concern that Imam Daiyee brings up. Essentially, when people come out they take on an exacerbated lisp or laugh.

“Most people don’t talk like that. It’s just all this pent up sexual frustration, that when they finally come out – they get a little wild.”

Every relationship has its ups and downs and Imam Daiyee understands that.

“It’s important to understand that each relationship builds on the other.” Imam Daiyee says.

The happiness in Imam Daiyee’s voice as he spoke about his boyfriend, reminds me of my wife. There is only so much anyone else will understand on what they mean to you.

Imam Daiyee pauses and then smiles.

“If things keep up. We’ll eventually get a nikkah [Islamic marriage].”

We may love differently, but we see it the same.

Category:

Share it:

Comments Off on VIDEO: Day 23 – Baitul Aman Masjid – 3114 Danforth Avenue, Scarborough

Category:

Tagged with:

Share it:

Comments Off on 30Mosques.com | Side Note: Breaking Dawn

By Bassam Tariq

The following photos and writing were done while driving through the Appalachians in West Virginia

We leave at dusk and head East. The car is quiet. All you hear are the sounds of the wind, the trucks passing and wipers making way in the fog. Clouds gather and your eyes get heavy. Don’t fall asleep at the wheel. Don’t fall asleep. Sleep will derail us. It will kill us.

Cutting through a mountain is work. Clouds live here. They are happy hugging trees, steeples and windshields. From this close, they are puffs of second hand smoke but healthier.

The rocking of the road tries again to put us to sleep but a light rips the clouds. Our eyes widen. We squint and then pull the visors down. The day begins and we are reminded that this is what we live for.

Category:

Tagged with:

Share it:

Comments Off on 30Mosques.com | VIDEO: Day 21: Singing Song of Praise

By Bassam Tariq

Singing songs of praise in West Virginia.

South Charleston is West Virginia’s largest Muslim community. After prayer, the imam sang a few nasheeds, Islamic songs of praise, with us in Arabic.

Khaldun Basha is a hafiz, someone who has memorized the entire Quraan. The mosque here brought Imam Khaldun from his native Syria to the community to lead them in prayer during Ramadan. When there are larger crowds at the mosque, the Imam said he likes to do some mawlids, songs that sing the praise of God and Prophet Muhammad.

“Whenever you say the name of Allah and Prophet Muhammad in a chanting way, these words become close to your heart and you’re able to make a connection to them,” the imam said.

We don’t speak Arabic, so if any of you guys do speak Arabic and would like to provide a rough translation of what the Imam is singing in a comment below, it would be greatly appreciated by us and our readers!

Category:

Tagged with:

Share it:

Comments Off on VIDEO: Day 22 – Abu Huraira Center – 270 Yorkland Boulevard, North York

Category:

Tagged with:

Share it:

Comments Off on VIDEO: Day 22 – Iftar – Sultan, Abdullah, Abdur Rahman – Abu Huraira Center

Share it:

Comments Off on 30Mosques.com | VIDEO: Day 20: Fireworks in a Parking Lot

By Aman Ali

My sincere apologies to the kid I almost shot in the face with these fireworks, lol.

Category:

Share it:

Comments Off on VIDEO: Day 21 – Madinah Masjid – 1015 Danforth Avenue

Category:

Tagged with:

Share it:

Comments Off on 30Mosques.com | Day 20: The MSA Experience

Category:

Tagged with:

Share it:

Comments Off on 30Mosques.com | VIDEO: Day 17 – Moments from Atlanta

By Bassam Tariq

Moments from the West End Mosque.

Visit 30mosques.com for more information.

Category:

Share it:

Comments Off on 30Mosques.com | Live Chat: Round 2!

Reminder: Live video chat at 11PM EST. Visit 30mosques.com for the feed. We might also be doing fireworks show for you all #30mosques

— Bassam Tariq (@curry_crayola) August 20, 2011

By Bassam Tariq

Thanks for joining our second live chat, over 300 people attended! If you missed it, click the “More” button below to catch it. Look forward to our next one at the end of the trip!

Category:

Tagged with:

Share it:

Comments Off on 30Mosques.com | Day 19: Allah Gave Us Honor

By Aman Ali

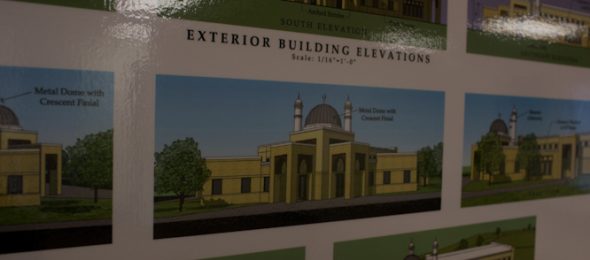

Welcome to Murfreesboro, Tennessee. You may have read about it or seen the CNN documentary about how a fringe group of local residents are trying to derail plans for building a mosque here. The construction site for the mosque has even been subject to arson and vandalism.

I was more interested though in finding out what was happening behind the scenes for the Muslims here. What’s it like to go from living in a small town in Tennessee to getting microphones and news cameras shoved in your face day in and day out?

I met the mosque’s imam, Sheikh Ossama Bahloul, in his office to chat about the whole ordeal. He speaks with a dense Egyptian accent pronouncing words like “the” as “ze” or any word with the letter “P” in it as “B.” But he cuts through the language barrier with his intellect. He said he’s well aware the opposition against the mosque isn’t necessarily an anti-Islam movement, but rather politicians stoking flames of fear to score some political points.

“They use the Muslim community in specific areas of the country as a tool in their hand to make specific achievements,” he said. “This is a strategy because of the White House election coming. 27 bercent of the American people believe the president is a Muslim, still! It’s craziness, yaani.”

When the controversy first erupted last year in Murfreesboro, Sheikh Ossama said nobody in the Muslim community anticipated how many news networks would come flooding in.

“The issue became too big,” he said. “The Jabanese TV, France TV, Australia TV came here. What is this, for what? In a way it’s ridiculous.”

I asked him if he did any interviews with Fox News.

“No,” he said before wagging his finger. “Audhu billahi minashaytan nirrajeem (Arabic for ‘Allah, I seek refuge and your protection from the devil’).”

The sheikh had me cracking up constantly with deadpan wisecracks like this throughout the entire interview. Hang out with him long enough and you’ll find out how much of an endearing goofball he is. A photographer was there that day asking us to pose seriously for the camera and I had to keep asking the sheikh to stop making Bassam and I laugh.

“Now this guy, he is looking scary,” Sheikh Ossama said while pointing to Bassam, who was sporting his Blue Steel pose for the camera. “Why you so scary? Don’t do that, I can get scared very easily.”

Sheikh Ossama said he mostly stuck doing interviews for CNN and the BBC. He chose not to do any interview with Al-Jazeera or similar Middle Eastern networks.

“We decided not to go to Al Jazeera or any of the Arabic channels because they would make it a big deal and make America look ugly,” he said. “It’s good to care about the country. American people are nice people. It’s not fair to say they are bad. I don’t want anyone to hate anyone. We must push for love and peaceful activity.”

This isn’t my first time meeting the sheikh. In September 2010, ABC News invited him and I along with a bunch of other people to participate in a Town Hall special on Islam. I chose not to say anything during the special because it turned into a theatrical shoutfest. If you saw the special, you saw the imam constantly trying to jump in and respond to all the ignorant things said during the taping. He told me early on, he often got heated in media tapings like these because it was tough to not respond to all the ignorance he was hearing.

“I couldn’t take it well in the beginning,” he said. “It was difficult for people to call me and give our Prophet Muhammad (peace be upon him) a bad name. It was tough to hear people say we can’t have a Muslim cemetery here in Murfreesboro because it will contaminate the water.”

But soon, he and other people in the community’s irritation to all the ignorance faded.

“People can be angry, but I intend to look at it from this perspective: I believe strongly that Allah chooses people for specific jobs. I believe that Allah chose us for this specific challenge. So in a way I felt Allah gave us an honor to deal with this challenge.”

“When people gave us fake allegations and lies, we were so comfortable because I don’t think it’s proper to make enemies because our life is too short and it’s not worth it. I might get mad here and there, but it’s not a big bercentage at the time because it’s not worth it.”

The Muslims here pray inside an office space inside a shopping center as they prepare to break ground on their mosque project in the coming weeks. I broke my fast in the evening alongside Salim Sbenaty. He’s 14 years old and I remember seeing him on CBS News last year about how he was actively standing up for the mosque and engaging the opposition.

“I’m huge on human rights,” he said. “That’s mainly what inspired me. It’s not more of my own religion that inspired me. If it was any religion, I’d act upon it because everyone deserves these rights.”

“Now how many times have you said that soundbyte in front of a camera?” I teased him.

Like me, Salim has done his own fair share of media interviews so we started riffing about all the silly questions reporters often ask us.

I get the question ‘How do you feeeeeel?????’ about a million times, he said. “Get it from the last guy, do you really have to ask me?”

But he doesn’t get annoyed by it, he added.

“I know that these questions may bring somebody towards better understanding what’s happening,” he said. “Even if I’ve said something over and over and over, it’s for another person that may have not heard it before.

He said he wasn’t prepared to handle all the media attention initially but there was a particular interview where he realized how big this whole Murfreesboro controversy really was.

“I think it was the one I did for Nickelodeon,” he said. “It was that interview when I realized, ‘Wow this is actually an international issue – Murfreesboro, Tennessee.’”

“Wow, Nickelodeon. You were interviewed by CBS News but the network that created Spongebob Squarepants, that’s what did it for you?” I riffed back.

When you’re doing so many interviews encouraging people to better understand Muslims, it’s easy initially to become infatuated with the aura of being on television. I asked him what he does to curb that.

“I try to remind myself that this is my civil duty,” he said. “It’s nothing special. I’m doing this for Allah and only Allah. This isn’t a priviledge or something that I chose to do. It’s my duty of sort.”

Now the “celebrity” in this community I wanted to meet was his older sister, Lema Sbenaty. She was on the CNN special and there’s footage of her grilling this lady running for office bashing the mosque project. Before coming here, I was in touch with her via Facebook where she kept calling me “Mr. Ali,” making me feel like I’m 26 going on 65. I was told she was outside, so I laced up my Puma sneakers and stepped out of the mosque to find her.

“Are you Mr. Ali?” she said pointing to me.

“Dude, I told you not to call me that!” I said. “Makin me feel like an old fart, jeez.”

“Well I dunno, I just saw the bald head and figured it was you,” she quipped.

After seeing her on CNN and learning about her courageous story, I had some burning questions for her.

“The most important question I have for you is, after the documentary aired… how many random people messaged you on Facebook with marriage proposals?” I asked.

She said she’s gotten more than 20! That’s almost twice what I’m getting.

“One guy from Tunisia said ‘I saw your interview and would like to meet your family,’” Lema replied while laughing incredulously. “I was on TV for 25 seconds. Who watches something that makes them want to go on the computer and send a proposal?”

She also gets several messages and emails from Muslim women thanking her what she’s doing. The challenge for Lema was learning to embrace the unwanted role of being a female Muslim role model.

“I don’t want to represent Islam in a bad way,” she said. “It was a big struggle, this whole idea of ‘Am I going to be good enough for these girls to look up to me?’ After the CNN interview, the sheikh came up to me and said ‘You have to pay attention to yourself now because people know who you are. So it’s good in some ways because you remain grounded and in check.”

A fringe but vocal group of people are pumping thousands of dollars into stopping this mosque from being built. As a result, the Muslims become victims of these people’s selfish attempts to exploit them for political gain. But I’m taken back by the relentless strength this community has. I asked the imam where their perseverance comes from.

“It’s good for the human being to recognize the limits in his or her ability,” he said. “I realize this situation is in Allah’s hands. I sometimes say ‘God, I don’t know much and I don’t know how to handle this, please help me’ and God will give you the help you need. If you are arrogant and say you can handle this on your own, you will not do as good.”

“Sometimes what people say can make me angry,” he added. “I’m not an angel. When I hear children in school being called terrorists and little girls coming to me saying they’re too scared to wear the headscarf, it hurts me and makes me angry. But it’s only for a few minutes. Allah chooses people to deal with specific challenges so we are grateful.”

Category:

Share it: