By Bassam Tariq

Beyonce plays in our car as we make our way out of Denali National Park. Aman is driving and controlling the playlist. “We ain’t got nothing but love. Darling you got enough for the both of us.”

Note: This post was written prior to the start of Ramadan

There is silence in our car as we look for a place to enjoy one of our last meals before Ramadan begins. Signal on my phone is fading in and out.

A guitar solo comes in.

“Sounds like the 80’s.” I say to Aman.

Aman stays quiet and concentrates on the narrow, winding roads. We may not be in the Chevy Cobalt this time, but even an SUV has to tread carefully through the winding roads of Alaska.

Another song from Beyonce plays. This one again is about love. “The best thing I had. You are the best thing I’ve ever had.”

Different beat, same schtick.

The music doesn’t fit the scenery. In my mind, it would be a melancholic indie track without any vocals. Or something pretentious and Icelandic. But instead, while we pass by the beautiful transcendent landscapes of Alaska we drown in a middle school dance playlist.

I would change the track, but Aman and I have a strict policy: whoever drives, controls the radio. Aman must feel the same pain in his ears when I am driving. He is just better at keeping the rants to himself more than I am.

We are different. From the way we drive a car to the comedy we find funny, there is nothing similar. Every TV and radio interviewer notices it within the first two minutes of talking to us. They ask us how it works and we just shrug it off by making a joke or two.

Aman reminds me of the Muslim Student’s Association I had in college. His interests mirror those in my MSA – from music to movies to sports. And the MSA for me was a safe haven from the rest of my college experience. It was our self-righteous playground, a home away from home. But it was a place that I never really felt like I had a deep connection with anyone. Other than praying with people and working to put on events, our friendships had limits because of our different interests. After moving to New York and meeting people that fall into a similar mold as me, Aman reminds me of the college days and all the anxieties with not fitting in.

Before the trip began, Aman and I sat together in a coffee shop and I asked him why he wanted to do this trip.

He spoke about it here in his last post, but when he asked me why I was doing it – I stumbled and talked about taking great photos of different communities and changed the subject. It didn’t really hit me until I reached Ted Stevens International Airport in Anchorage that I have no idea why I am here. The gimmick of visiting 30 Mosques in 30 days in 30 States was fun last year, but something tells me we need to dig deeper.

—

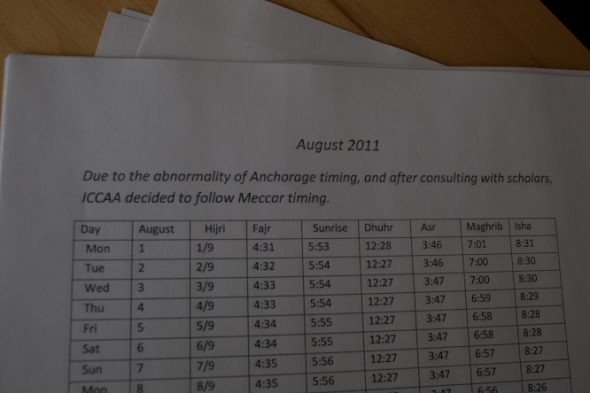

Anchorage has only 3,000 Muslims and the majority of them are from abroad. They have been painstakingly working for the past six years to build a real mosque for the community but have had no luck. Most of the congregants are cab drivers, plumbers and teachers. So it becomes very difficult for them to raise the needed funds.

“We feel a little homeless.” Said one of the brothers I met when I probed him on why they actually needed a mosque. The two rooms they occupied right now seemed more than plenty for the community. But the ability to claim a space and call it their own gives a small and disenfranchised population the respect and dignity they are yearning for.

The night before, I was hanging out with a local Pakistani guy about my age. He was anxiety-ridden and didn’t really enjoy being in Anchorage. He had been here for 12 years. He graduated from high school here and also went to college in the neighborhood. A part of him wanted to leave Anchorage but there were too many responsibilities that he had to look after. While we drove across town he told me about finding love in this small town and how it was difficult for his parents to accept it.

He stops in the middle of his thought and asks me, “How do you do it? Why do you believe?”

I paused, not sure what to say. I understand where his question comes from, we both met each other at the mosque only a couple of hours ago. He doesn’t owe me anything about his life. As far as we both know about each other – we are Muslim enough that we identify with a community and show some semblance of worship in the public. That pretense is enough to halt a deep conversation about love and emotions associated with breakup.

It’s hard not to see mosque as theater. There are costumes, grand performances, and a role that everyone seems to play. Not to say that the experience isn’t authentic, but it would be tragic to undermine the entire Muslim experience in Alaska or in any State just by basing it on the mosque in town. So when meeting someone there, there is a quiet handshake that assumes that the context of our friendship begins and ends with Islam. Which can be quite dangerous in a small community where it’s easy to feel left out when there are very few people that look or believe in something similar to you.

—

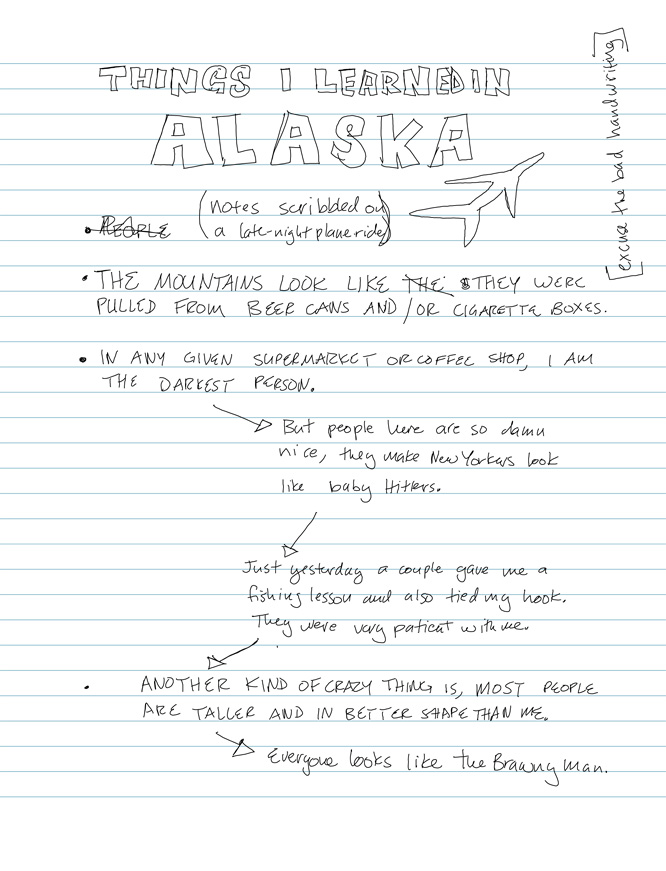

I now sit in a supermarket in Wasilla, Alaska. I am barefoot and my pants are rolled up. We went fishing in Talkeetna and caught nothing. There is a blog post that I need to put up, so I begin writing and uploading video like a mad man. A group of boys sit around the corner from me and stare. In any given space in Alaska, I will probably be the darkest person there. It was obvious that I wasn’t a local from Wasilla.

It took only a minute or two to strike up a conversation with the guys. They were all close to 18 years old and fit the classic mold of small town misfits. One guy named Lance, a lanky, long haired boy with strands of blue in his hair, began to speak to me about a social networking site called MyYearbook.

“It’s kind of like facebook, but a better way to meet random people.”

He was posting photos of himself shirtless with his hair covering his eyes.

“You can be anyone on the internet, eh?” I joke with him.

Lance smiles and goes back to playing an online role playing game.

Sitting next to him were these identical twins. They began asking me about my thoughts on French cinema and music. They shared Youtube videos of what they considered to be the next Jim Morrison and started to speak to me about artificial intelligence. The curly haired twins were named Arthur and Oliver.

Oliver is an artist. He pulls out his portfolio and begins to go from picture to picture to explain the mathematical reasoning behind them. His rant goes over my head, but I continue nodding.

“You guys are just too excited about meeting this guy.” A lady friend of the twins says. She has four piercings in her nose and two in her eyes.

They ignore her and continue talking.

Oliver is working to implant metal into his nails so that he can better understand his brainwaves.

“Are you kidding?” I ask.

“No, I am a Transhumanist. We are a group of people working to become better than human.”

Oliver continued on the ideas of Transhumanism and how it can save lives and help us reach our true potential. His brother stood around, quiet and collected.

“Arthur, what about you?” I ask, “Are you a Transhumanist?”

“Yeah, there are some cool parts of it, but I kind of have bigger things to worry about.”

I look over at the pockets of his skinny jeans and notice a large knife sticking out.

“I have to be careful walking the streets of Wasilla, not many people get me here. I was just chased by skinheads yesterday.”

Arthur is a crossdresser. He jokes that I caught him on an off day.

“So you’re the only cross-dresser in Wasilla?”

“Well, there is another guy, but he is usually too doped up on crack for people to take him seriously.”

Everyone at the table laughs.

All the kids go to a special education High School in Wasilla. Lance brags that no one there can tell him what to do.

“This town is so f**king white.” He snarks playing his online game.

I ask Oliver and Arthur if they go to the same school as everyone else.

“We kind of went from being home-schooled to un-schooled.” Oliver says.

“We’ve had to teach ourselves everything we know about this stuff. Our parents don’t like it, but they don’t have much say in our lives.”

I look at the clock and see that it is time for me to get out of here, I begin to head out and the kids follow behind me.

“Where do you all live?”

“In a tent.”

“What?”

“Yeah, in a tent in our sister’s yard with our mom and dad.” Arthur says, “we got kicked out of our house last Christmas and have been homeless since.”

The twins walk me to my car.

“Have you all ever thought of leaving Alaska? Maybe Portland or Seattle would be more accepting of your ideas?”

The twins shrug.

“This is home.”

I drive out in the car and see the small group of misfits sitting around the on-clearance plastic patio chairs. They kick the chairs and laugh at bad math jokes.