By Aman Ali

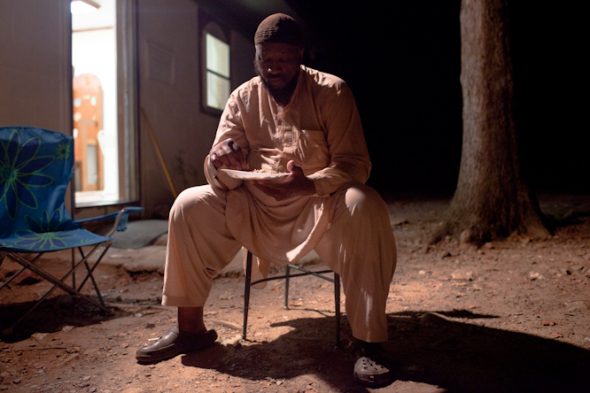

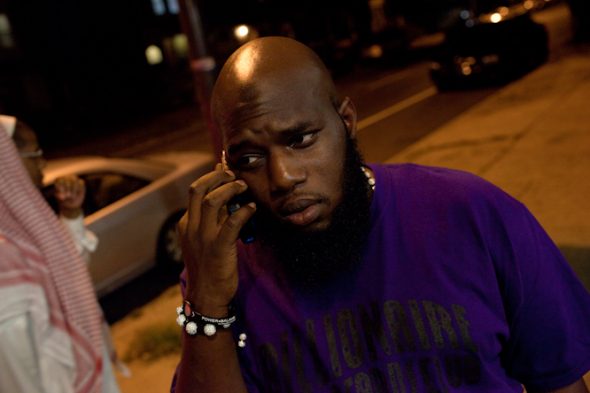

Freeway puckered his lips and stroked his fleecy facial hair as I asked him about the purple “Billionaire Beards Club” shirt he was wearing. Breaking out in the hip-hop scene on Jay-Z’s Roc-A-Fella label in the early 2000s, his distinct look brands an image into your brain just as much as his rhymes.

“I’m a Muslim,” he said. “So this beard, it’s an attribute of a Muslim. It’s a part of me, so I’m just doin what I’m doin normally.’

“Where I’m from here in Philadelphia, this city has a huge Islamic community so its normal,” he added. “Especially when you walk out in the streets out here, people know who I am so they don’t look at me like I’m going to blow up a plane.”

The Philadelphia Muslim community has its own charm to it. They’ve got this in-your-face and unapologetic pride in being Muslim. What also stands out is the community’s heavy influence from street culture. It’s not uncommon to see someone with a long beard and traditional Muslim garb accessorized by gold teeth and an iced-out watch. It’s hard to explain with words though, what may seem odd anywhere else is the beautiful norm here in Philly.

I met Freeway in downtown Philadelphia alongside three of his friends at a local Indian restaurant. One of them was Freeway’s barber, who points to my face and asks me where I got my beard lined up. I told him I did it myself in the bathroom when I woke up today.

“Well, I might have to ask you to grab a chair in my shop then,” he said with a laugh.

Philadelphia wasn’t a scheduled stop on our tour, but when Freeway’s manager reached out to us asking if we wanted to meet him, it was a no brainer for me to hang out with one of my favorite rappers I listened to in high school.

Freeway has a vibrant and unshakeable demeanor when he’s onstage rapping but in real life he can be a reserved man of a few words. He stares across the room and rubs his hands together in the air as he repeatedly takes a few moments for deep thought.

Freeway embraced Islam in his teenage years while growing up in Philadelphia. He prowled the city’s hip-hop scene battle rapping anyone who wanted to step into the ring with him.

“I just loved the music,” he said while reaching for a piece of tandoori chicken. “It was just something I knew I was good at. I always felt like I had a shot so I kept working at it. Whenever someone else blew up, I never hated on it. I always felt like I’d get my time too.”

Soon, rapper/mogul Jay-Z got word of Freeway’s talents and signed him to Roc-A-Fella records. Freeway became an overnight success with producers like Kanye West maestroing his debut album. That’s when he decided to go on Hajj for the first time in 2004 with Jakk Frost, a Philly rapper sitting next to him whose bond with Freeway goes beyond music.

Jakk Frost is a beast of a man. Words come out of his mouth with a thundering boom and just looking at his hands I know he could probably crush someone like crumpling up a piece of paper. But he offsets that with an affable tone in his voice. Speaking to him you get a sense of an incredibly deep sense of loyalty and friendship to Freeway, which is why Freeway brought him on Hajj in 2004.

“I wanted to go on Hajj because it’s part of my religion,” Freeway said. “It’s one of the five pillars of Islam and I finally had the free time and the money to do it.”

“And he had somebody to get on his nerves about it, hahahaha,” Jakk Frost said with a bellowing laugh.

Being in Saudi Arabia to make the holy pilgrimage was an eye opening experience for Freeway, especially when visiting the Kabah, the Islamic holy house Muslims all around the globe pray towards every day .

“When I got to Mecca and saw the Kabah, I just broke down and busted into tears,” he said. “I mean, this is the house that Abraham built. I’ve prayed to this place for a large part of my life. It just touched me man – it was a beautiful experience.”

It also started making him think about the decisions he was making in his own life.

“I buckled down,” he said. “Someone told me over there, ‘If you go back home and you’re doing the same things you were doing before, then you didn’t get anything out of your Hajj. I became more aware of what I was doing as far as how I was dealing with people and I tried to cut out a lot of extracurricular activities I was doing. You know, I was just trying to make my life better.”

He was one of the hottest rappers on the scene at the time but that Hajj trip also made him think about walking away from music altogether.

“When I’m rapping, people listen to my music and could be doing other things like remembering Allah,” he said. “The time I take to create the music, I could be doing other things too regarding Islam.”

Roc-A-Fella records slowly started to crumble shortly after because of internal management problems much to the shock of Freeway and fans like myself all around the world.

“We didn’t expect it,” he said. “We thought Roc-A-Fella was going to live forever. Just being in the mix of it, we thought it was never going to stop. “

Freeway is now signed to Rhymesayers Entertainment, an independent label featuring fellow 30 Mosques friend Brother Ali. He said he enjoys what he’s doing now and there’s no animosity with his Roc-A-Fella friends of the past.

“I’m still cool with everybody,” he said with a nod. “I talk to Jay still, so we’re good. The whole label thing may have fallen apart but the strong will survive.”

“Right now, I’m just grateful that 10 years later, I’m still relevant,” he added. “I’m thankful I still get 3-4 shows a month. And that sense of thankfulness, it comes from Islam.”

Freeway has never been ashamed of being Muslim, but it wasn’t until recent years when he decided to talk more publicly about his faith.

“I think it has a lot to do with me getting older and more mature,” he said. “It just naturally leads to me embracing it more.”

If he’s embracing the title of Muslim more, I asked him then about his lyrics. Some of his older work focused heavily on references to drug dealing and violence.

“These days, I really think about what I’m going to say because I don’t want to give people the wrong impression of something. Right now, what I rap about is my life in general. Being from the hood, I still have everyday struggles. I lost a lot of friends (to gun violence). Matter of fact, I just had a cousin that was killed.”

Being in the limelight is always a struggle for any Muslim wanting to keep his or her ego in check. Freeway said he tries to do it by reminding himself of a point early in his career. There’s an infamous video from 2001 where Freeway and his Roc-A-Fella labelmates walked into a radio station for an unforgettable freestyle session. But soon after in his career, there’s a video just as unforgettable of Freeway arguably losing a freestyle battle to a rapper named Cassidy.

“When I sit back and look back at that, I realize that was from Allah,” he said. “He always balances things out for me. Before I get too big headed he always puts me back in my place.”

“Looks like you’ve got this guy to keep you in your place too,” I quipped while pointing to Jakk Frost.

Jakk kicks his head back and thunders another laugh.

“It’s a reminder that Allah can bring people up and just smash them down like they’re nothing,” Jakk said while hammering his fist onto the table. “Like they’re nothing.’”

To this day, Freeway said he still struggles with why he’s doing music. Part of him still feels like what he’s doing is un-Islamic.

“The main reason I do music right now is to feed my family and I’m good at it,” he said. “No I don’t want to do this forever. Eventually I want to get my life together and life my life according to how a Muslim is supposed to do. But while I’m doing it, I’m doing everything else to the best of my ability to be a good Muslim – pray five times a day, fast during Ramadan, make Hajj.”

By Freeway’s side throughout the entire struggle has been Jakk Frost. The two met around 1996. For a while, it was Jakk Frost that was the better known rapper and Freeway the lesser known one. Now that the roles have changed over the years, I asked Freeway what he does to curb potential tension between the two.

“He’s my brother and he means a lot to me,” he said. “We’ve done so much together that’s more than music. All my friends, we have a bond, that sense of brotherhood that extends from Islam. That’s our core. That’s what we have that a lot of people don’t have.”