By Aman Ali

It’s been over 11 years since Imam Jamil Al-Amin, known during the Civil Rights era as H. Rap Brown, was arrested for shooting two Atlanta officers.

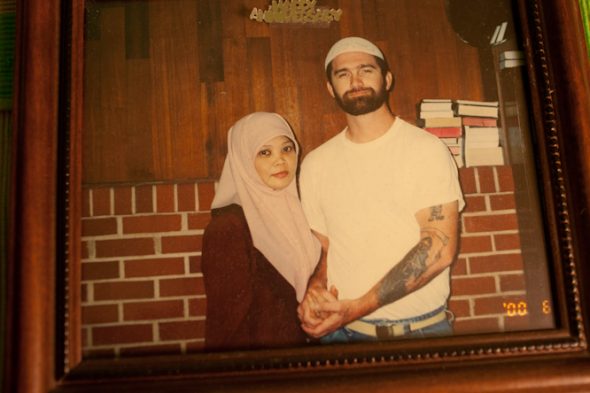

His wife Karima of over 43 years spoke with me, folding her hands in her lap and opening up about how she deals with his controversial conviction.

“Well, it’s in Allah’s hands and we submit to that,” she said. “When you submit, you take anything and everything that comes your way. Nothing throws us.”

I first learned about Imam Jamil in high school through hip-hop. Public Enemy put out a track in 2002 where Chuck D says “Jamil Al-Amin, nah’ mean?” Well, a kid like me from a white Ohio suburb didn’t know what he meant, so I Googled the name. Before he was Muslim, Jamil Al-Amin was H. Rap Brown, a civil rights activist and chairman of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. He was controversial for his views on race and was often accused of inciting riots.

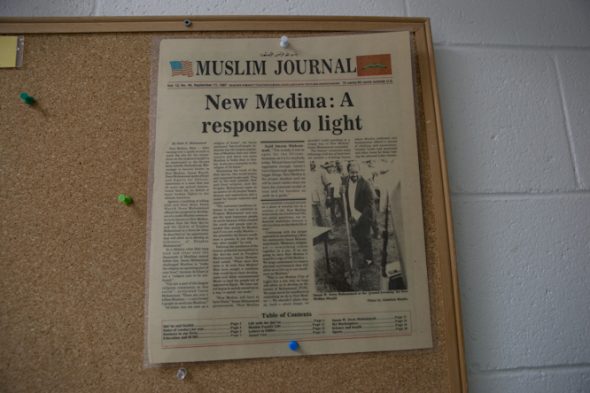

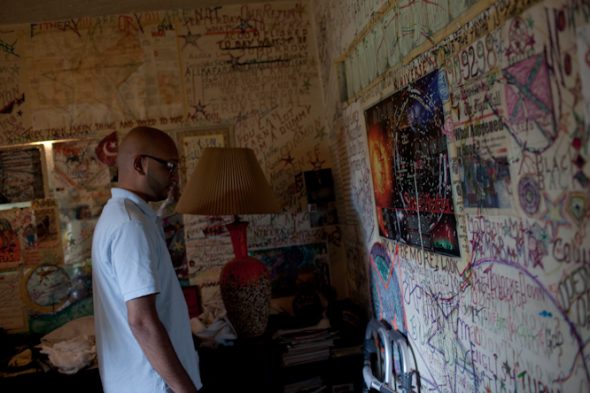

In the 1970s, he and his wife embraced Islam and established a mosque here in the West End of Atlanta. It was one of the first mosques in the area to hold the five daily prayers in Islam known as salat. Among many things, the mosque under Imam Jamil’s leadership cleaned up crime in the neighborhood and many convicted criminals abandoned their pasts and embraced Islam. On the national level, he tried to bring many national Muslim groups together.

“He always felt if we prayed together and fasted together, we could be a political force,” Karima said. “He never felt we were outnumbered, just outorganized.”

I asked the current imam of the mosque, Nadim Ali, what it was like to deal with Imam Jamil getting locked up.

“He trained us for this,” he said. “When he got incarcerated, he told us ‘It’s still five a day. It’s never been about me, still gotta pray five times a day and establish your salat.’”

(Side note: Imam Nadim Ali is an incredible singer and in the coming days we’ll be posting a video of a quick song he did with his fellow group mates.)

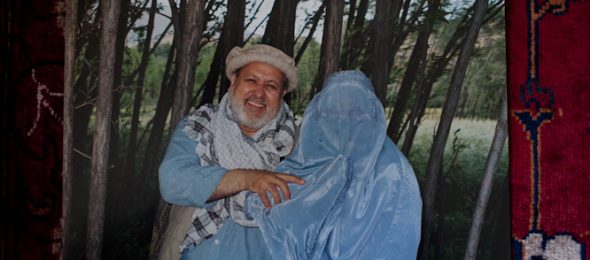

The following are photos from the mosque community that Imam Jamil help start.

You can read all about Imam Jamil here and about his controversial arrest and conviction here. It’s important for us to go beyond the headlines and explore his relationship with his wife and his spiritual impact on the people that know him.

Since the beginning, Karima said Imam Jamil has always been a political target. She said she never worried about his safety fielding death threats and getting arrested after speeches because it came with the territory of being a public figure at the time.

“We were young and on top of the world,” she said. “I never really thought in terms of something happening to him.”

She added she felt the same way when he was arrested in 2000. The family had just returned from a dinner at Red Lobster when Imam Jamil went to the mosque to lead prayer and check up on a local Islamic goods store nearby. Moments later, Karima, who is also a practicing attorney, learned he was arrested.

“The story about how he was arrested is fuzzy,” she said. “The main thing is he maintains his innocence and he was not the person who did those crimes.”

I told Karima I’m sure dealing with the arrest ever since has been a rocky journey of emotional ups and downs for her.

“I think because my whole background is about struggle, I don’t see ups and downs,” she replied. “Allah has the plan and he’s inside prison still making a difference with people.”

Imam Jamil was first incarcerated in Georgia. Many people he met while in prison embraced Islam after living with him.

“People tend to pay attention to people they think might be a celebrity or well known,” Karima said. “But I think it goes beyond that. It’s the way he was able to connect to people.”

In 2007, the federal government intervened because they felt he was too high-profile of a person to be locked up in Georgia. So they transferred him to the Supermax Prison in Colorado. Regardless of how you feel about Imam Jamil’s history, it seems way excessive to me to lock him up in the same prison as Terry Nichols, the Oklahoma City bomber, Ted Kaczynski, the Unabomber, and several other convicted terrorists.

“That’s the thing,” Karima said. “You and I can make distinctions but the federal government does not.”

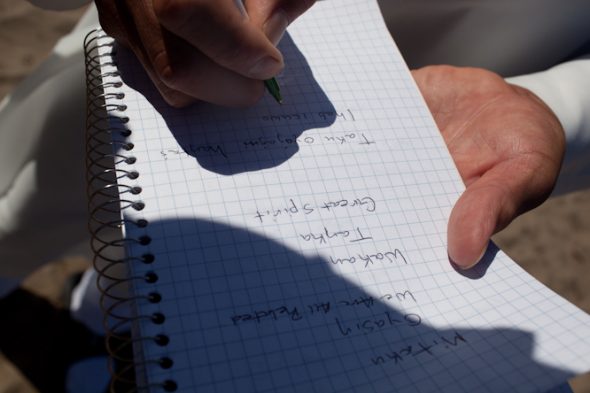

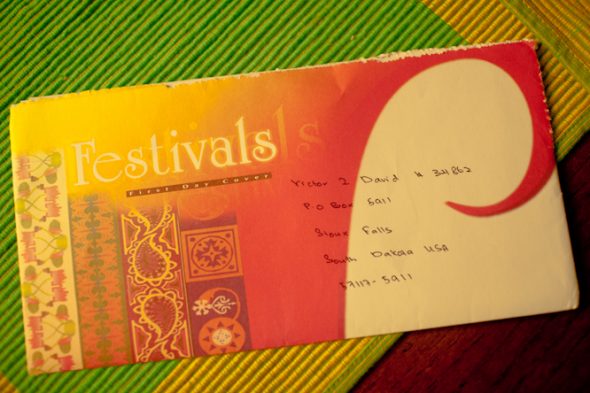

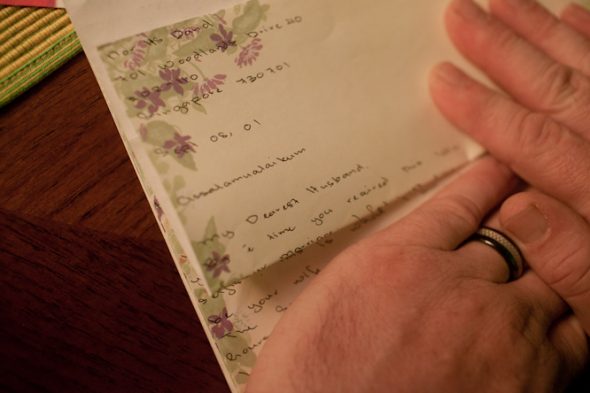

Supermax gives Imam Jamil two phone calls to make a month. Karima said she and her son try to visit him in Colorado whenever they can, but shelling out around $2,000 each time to travel there gets costly. Many people write Imam Jamil letters, including one of the mosque’s congregants here Qaasim Griggs, 8. Qaasim told me he learned about Imam Jamil from one of his uncles and wrote to Imam Jamil about how he liked his name. The imam wrote back.

“He said that he has a feeling I’m going to be a strong boy,” Qaasim said with a smile. “It made me feel happy.”

I asked Karima after over 43 years of marriage, what is it that she loves about Imam Jamil.

“He always has had the thought pattern “As long as I can make my five, I’m going to be ok,” she said. “He represents commitment to the degree you can’t even put a label on and that’s why I’ve been with him since I first met him in 1967.”