By Bassam Tariq

Note: There are many families that have helped build the Cedar Rapids Muslim community. Unfortunately, I was only able to meet with a small portion of them. So please take these small accounts and stories as part of a larger history.

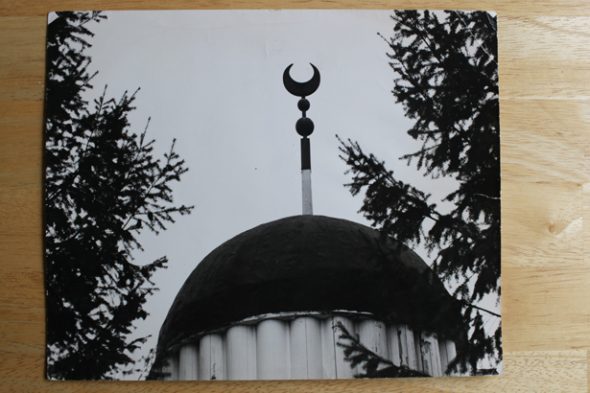

Many mistake the Mother Mosque as being the first mosque in North America, but as we blogged a couple of days ago, Ross, North Dakota was the site of the first mosque in 1929. What makes the Mother Mosque so important though is that it’s the longest standing mosque, established in 1934.

Throughout the 1800′s there were many Muslims that emigrated to the states to work at factories, railroads, etc., but very few of them were able to create sustainable communities. The Mother Mosque is a nationally recognized historic site and is preserved by Imam Taha. Since the Cedar Rapids Muslim community moved to a larger mosque, the Mother Mosque now serves more as a historical landmark and cultural information center.

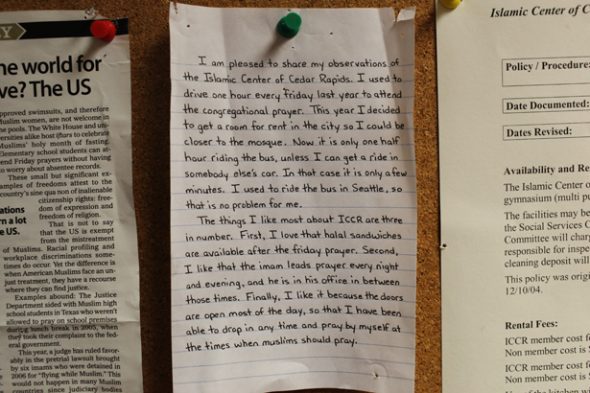

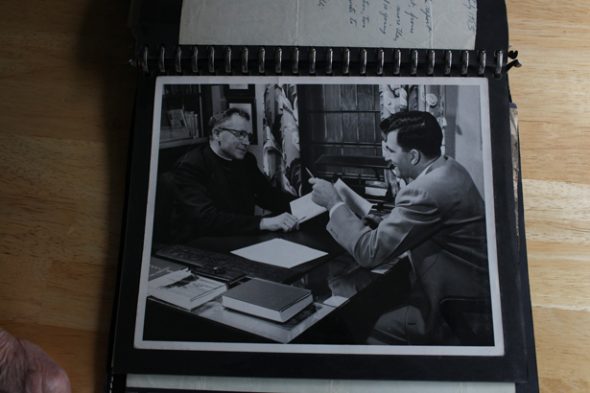

The basement of the Mother Mosque is lined with photos and news pieces showcasing a rich history covered by the local papers and tv outlets. From the first news clipping and photo of the congregants outside of the mosque to pictures of the aftermath of the drastic Iowa floods that desecrated hundreds of important books, Imam Taha and the community have done a great job preserving the history of the mosque.

Unlike most of the Muslim communities in America, Cedar Rapids is home to a large community of third, fourth or even fifth generation American Muslims. Aman and I, both coming from largely first generation Muslim communities, wanted to learn more about these folks.

Today, on a cloudy Labor day, we sit with Fatima Igram, a third generation American Muslim, at her house as she shares some important photos with us from her community. .

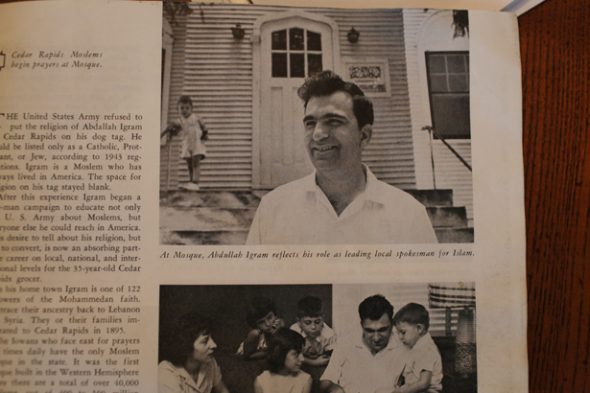

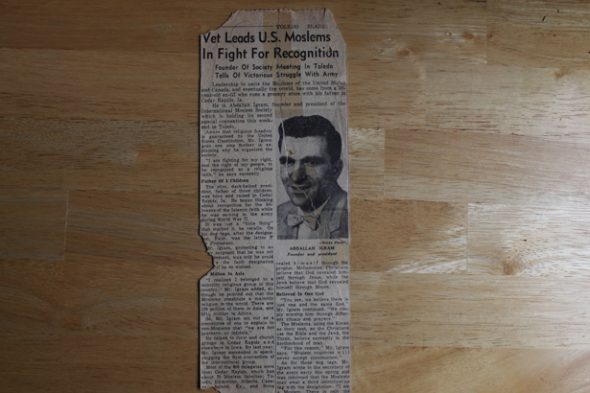

Her father, Abdullah Igram, was in the military and was stationed in New Guinea during World War II. When he was getting his dog tag made, he was asked to claim his religious affiliation with either a P for Protestant, J for Jewish, or C for Catholic. Abdullah said he was a Muslim and asked for an M to be engraved. The military couldn’t produce an M on the tag, so decided to leave it blank. For Abdullah, the idea of dying abroad and not receiving the right burial was terrifying.

Thankfully, Abdullah safely arrived back to Iowa after the war. A couple of years later he wrote a letter to President Eisenhower persuading him to add the M option on military dog tags. Soon enough, Abdullah received a letter from the President’s secretary thanking him for the suggestion and the M option was added.

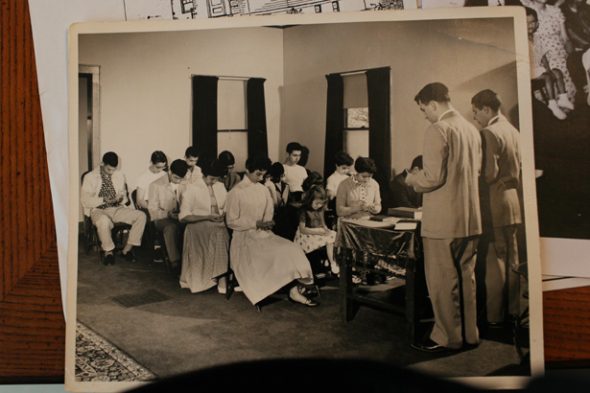

Abdullah Igram, a Syrian American, was born in America and became somewhat of an ambassador for the Muslims to the larger community. He was one of the first kids in the community to complete the Quran in Arabic. Afterwards, he taught basic aAabic and Qur’an classes in the basement of the mother mosque.

Aziza Igram, Abdullah’s wife and Fatima’s mother, came to the US when she was nine years old. She is now 82 and has been working at the Yonkers department store for the last 31 years.

“Uf, I think I’m going to quit soon.” she says to me.

Aziza is a petite Lebanese lady who loves talking about her kids, grandkids and, well, great grandkids. She is a hard worker and Fatima, her daughter, has been trying to convince her for years to leave her job.

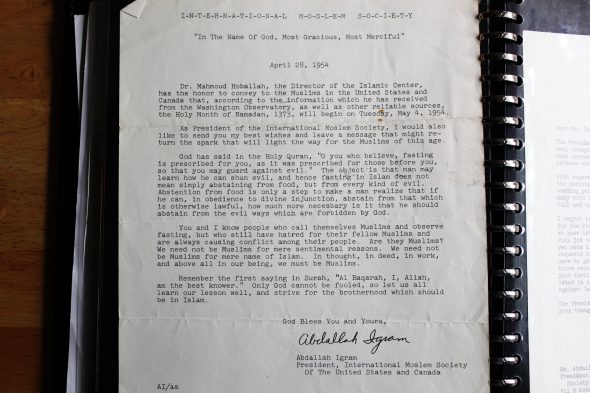

Aziza has a large collection of her husband’s letters and documents. There was one letter written to an official in DC talking about the lack of unity when it comes to moon sightings during the month of Ramadan – the letter was written in 1954. So, yes, ease up fellow Muslim readers, your local uncle was not the pioneer of moon sighting quarrels. We learned it from our forefathers, clearly. 🙂

On our way out of Iowa, we stop at a furniture shop owned by Naji Igram, a third generation Lebanese American Muslim. Back in his day, Naji was a body builder who entered competitions regularly. At one point, he became the third runner up in Mr. Midwest.

“Ahh, I stopped it,” Naji shrugs, “there were more important things for us to spend our time on.”

Naji is a laid back guy who is known for his large hands. In fact, before knowing his names and his accomplishments, I was told about how large his hands are. Though he wouldn’t want me saying it, Naji has been integral in helping the Muslim’s in Cedar Rapids progress.

“Our families didn’t know much about Islam. They just knew the bare basics.” Naji says to me sitting a nice dining table on display, “They came to America as peddlers and grocery store owners, they were busy trying to survive.”

Many of the Lebanese families ran grocery stores in Iowa. Naji himself owned a grocery store, but, like many muslims, left because of the conflict of selling alcohol and lottery.

At the time, the Mother Mosque had a small turnout for Friday prayers, and small lectures on Sundays. There were makeshift arabic and quranic lessons, but nothing substantial was happening.

“That wouldn’t have been enough for our community to survive. We needed more.”

In the 1960′s and early 1970′s, the small Iowan Muslim community found a large number immigrants coming from South Asia for work.

“Many of the Pakistanis would try to correct us, or tell us what to do.” says Naji. A classic example of the clash of Immigrant v. Indigenous.

“but they were kind of right. We didn’t know much and needed to learn more.”

“We had a big divide around then, those that liked the way things were before, and those that were willing to progress in their Islam and their practice.”

According to Naji, those that were okay with the earlier ways of the community left and those that were willing to progress stayed and built the mosque into what it is now.

The Cedar Rapids Muslim community is large and vibrant. Aman and I joined them last night for dinner and were amazed by the diverse congregation we saw. For dinner, we had rice pilaf, tandoori naan, butter chicken, goat with gravy and rice pudding for dessert. It was clearly a Pakistani/Indian menu and a meal the entire congregation seemed to enjoyed.

“I’m optimistic about where our community is going,” Naji says, “our kids, they know more than we do. Actually, our kids’ kids know more than us. And that’s promising.”