By Aman Ali

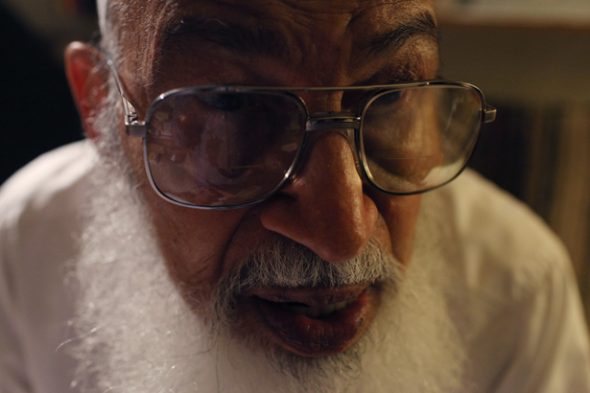

Sheikh Abu Omar counted on both of his hands how many times he came close to dying. The 80-year-old man has escaped drowning, political assassinations and even a fatal health diagnosis in the 1970s that remind him how blessed he feels when he wakes up every day.

“Allah has protected me,” he says as he puts his left arm around me and points his right index finger into the air. “He did not want me to die on any of those occasions. If that doesn’t convince you to have faith in God, then I don’t know what does.”

Sheikh Abu Omar Al-Mubarac is a pioneer of the Muslim community in Denver and is still an active volunteer here. He grew up in Iraq and escaped the country in the 1960s when the Baath Party, Saddam Hussein’s ruling group, wanted him dead because he refused to side with them. He’s been living in the Denver area since 1968.

Sheikh Abu Omar was actually an officer for the Iraqi government and said he knew Saddam as he worked his way up the ranks in the Baath Party in the 1960s. But he couldn’t side with what the party was doing, and like many dictators that rise to power, the Baath Party tried to kill him because of his opposition. He escaped and moved to Colorado and got a job working for the state examining workplace safety claims. To this day, he still lobbies the state government on union and workers issues.

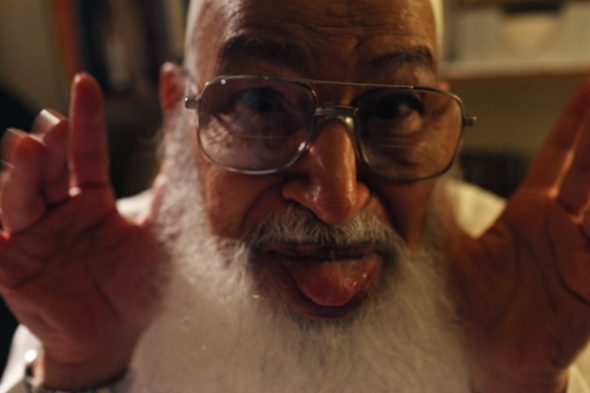

His lips pucker every time he smiles and he slaps me on the back with each joke he tells. I ask him what were his reasons for staying in Denver for so long as opposed to anywhere else in the world. He said he loves living here, he just gets irritated with the weather here.

“The weather here is like a woman,” he said. “She never knows how to make up her mind.”

As he said that, in the back of my mind I start thinking about how majestically beautiful the drive into Denver was. We got stunning views of the Rocky Mountains coming into town.

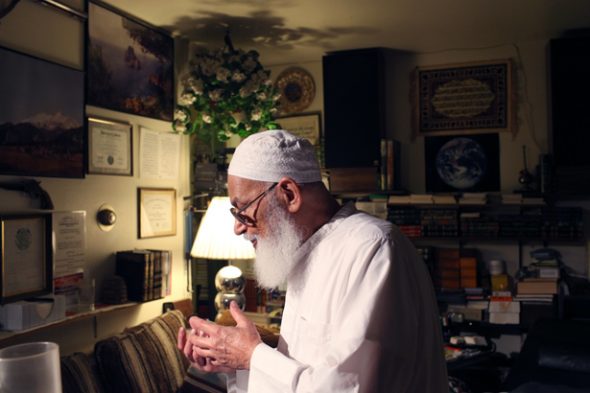

Our plans of where we’re going to sleep fall apart at the last minute and the sheikh is gracious enough to let us sleep at his place overnight. His cozy home is so crammed with files and books from his services center that you have to come up with clever ways to maneuver around the place without stepping on something. There dozens of framed certificates and civic activism signs that cover just about every open space on the wall.

“If you’ll excuse me, it’s night time and I just need to take my medication,” he said while trying to avoid stepping on a box of files in front of the kitchen. “I just need to take my birth control and Viagra, and then I’ll be fine.”

He comes back and sits on the couch as Bassam begins to take pictures of him.

“My face is going to break your camera,” he says with a laugh before sticking out his tongue for a goofy pose.

For an 80-year-old man that’s seen so much in his life, I asked him where he gets his optimism from. He points to the rectangle rug that’s in front of the couch.

“See this? It’s about the size of a grave,” he said. “Whenever my head gets big, I think about my grave. Because when I die, no matter what I have in life, I can’t take my possessions to the grave with me.”