By Aman Ali

Bassam and I stress over our planned visit to Fargo, North Dakota. We didn’t expect our rental car to break down in Montana and the time it took to fix the car (thank you all for the prayers!) is making us late. It takes 11 hours to get to Fargo and getting there at a reasonable time is simply not going to happen now.

Instead we program our GPS to take us to Ross, North Dakota – a town with a total population of 48 people during the last U.S.Census. When my brother got married, I think there were more people sleeping over at our house that weekend than live in Ross.

Ross is home to the first mosque that was ever built in the United States. A Syrian farmer by the name of Hassan Juma immigrated to the U.S. and settled in Ross in the late 1800s. More Syrians came into town shortly after and the community built a mosque in 1929 after spending years praying in each other’s basements. It was later demolished in the 1970s but there’s a Muslim cemetery nearby where many of the original community members are buried. In 2005, a new mosque was built on the same land as the original mosque.

Bassam and I don’t know anyone who can help us find this place. Google Maps barely even knew. To our luck, a local pastor got us in touch with a woman named Lila who is the caretaker of the place. She can”t meet with us at night to open the mosque but she kindly let us visit it from the outside.

We’re driving through Ross amidst a barren landscape and take a turn down an empty dirt road. We have little idea if we’re going the right way but I keep my eyes peeled intent on finding the place.

About a quarter mile down the dirt road, my jaw drops as we find the place we’re looking for. Standing in front of me is a cube shaped mosque with a helmet dome and mini-minaret pillars on top. My heart is punching in my chest as I begin to walk towards it.

A sign to the left of the door dedicated the building to “Sarah Allie (Omar) Shupe.” I don’t know much about her but I remember reading she was instrumental in making sure this new mosque was built. I think about what she must be like and for some reason, I begin to feel like I’m falling. Fast. It was the same plummeting feeling I got when I was 18 and a skydiving instructor shoved me out of an airplane for the first time.

I don’t know why I’m falling. Maybe it’s because I’m standing in front of a place that’s taking me back in time.

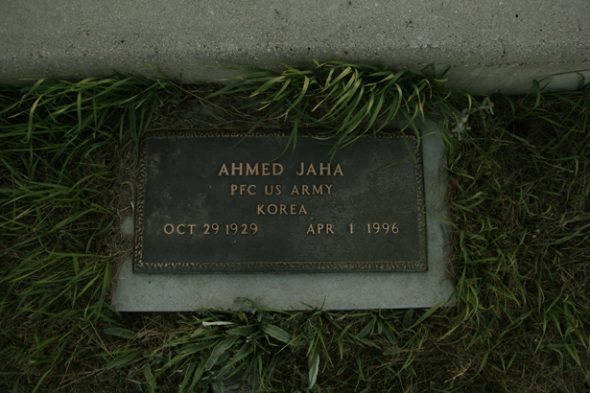

I find the cemetery about a hundred feet from the mosque. I begin reading the names on the tombstones and the birth dates below them. 1882, 1904, 1931. Each of them has a star and crescent symbol at the top of the stone reflecting a Muslim was buried there.

Some of the stones indicate the Muslims buried here were veterans that served this country in armed conflicts like the Korean War. It takes several seconds for my brain to realize tears are spilling down my face. I feel ashamed to have known very little about this place until I got here.

Ross is a small town and we know virtually no one we can stay with for the night. We drive around for miles and can barely find a gas station, let alone a hotel.

We’re told the nearest hotel is about an hour away in Minot, so we head there for the night. I begin to write the post about our visit to Ross but feel I incomplete. We know very little about this enchanted place, so we ask Lila to meet us in the morning to learn some more about it.

####

Lila and her son Greg stand by the mosque as we pull our car through the opened gate the following morning.

She’s an olive skinned woman who bounces her arms along with her cheerful tone. She flashes a radiantly youthful smile and slaps her knees every time she laughs.

Greg opens up the door to the mosque and Bassam and I pray inside to pay our respects to the place. I walk around the stone room and am fixated on how serene and simple the place is.

I walk back outside and again read the name of Sarah Allie (Omar) Shupe. Lila points to the name and pauses.

“That’s my mother,” she said. “She was the driving force for this place.”

This mosque was built in 2005 on the same land the original mosque was built on. I asked her why the original one was demolished in the 1970s.

“Oh, I’m not going to go there,” she said as she looked away. “I wasn’t there at that meeting so I don’t want to get into it.”

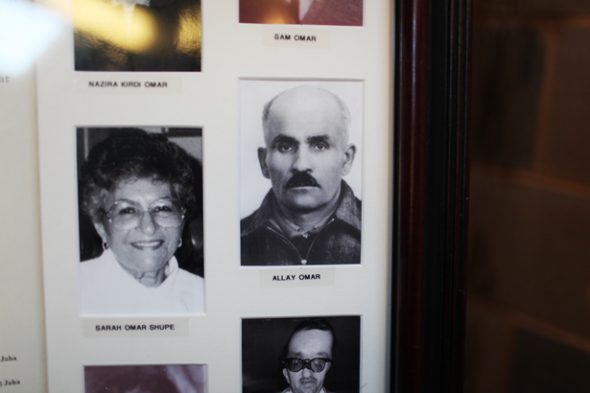

I can sense the question is a sensitive subject, so I decide not to pry. Instead, Lila takes me inside and shows me a framed collection of photographs of some of her relatives and family friends who helped pioneer the community here. She points to one of Allay Omar, her father, and one of her mother Sarah.

Allay Omar grew up in a region a part of Syria that is now modern day Lebanon. Waves of Syrians came to this country in the early 1900s once the United States lifted its ban on immigrants from Arab countries. Syria at the time was under control of the Ottomon Empire in Turkey and many Syrians fled to the U.S. to avoid getting drafted in the Turkish army.

Lila’s father and other immigrants came to North Dakota because the Homestead Act gave people up to 160 acres of land after taking care of it.

Greg explained tensions would often flare among the Syrians and other immigrants here not over their race, but over resources like land and livestock. As Greg speaks, Lila uses her motherly instincts and sways nearby mosquitos off his arms.

Earlier we had written about Greg saying tensions among immigrant farmers here over resources instead of race. In a follow up conversation with us, Greg said this to clarify, “With the remoteness of this place you had to depend on your neighbors and they had to depend on you. There was no time for racism, as it took a backseat to survival. There were no ambulances, no flight for life helicopters, no telephones.. no electricity or propane for that matter. These brave people learned to live together and learned to ignore the outward appearance of a man because it is the inner man that counts.”

Lila was born and raised in the area and still lives a little over a mile away from the mosque. Her high school graduating class had five people in it. I ask her what that was like, being not only the only Middle Eastern kid, but one of the only minorities in town.

“I knew I was darker skinned than most people, but I never saw it that way,” she said. “I am who I am.”

These days she says it frustrates her about what people think about people in the Middle East being male chauvinists and anti-Semitic.

“They say the men are oppressive towards their women over there and I’m sure that happens,” she said. “But I never had that experience. My father treated us like princesses. My father had Jewish friends and taught us to love them. I have Jewish friends too and I’m always going to have Jewish friends. I was taught to love everyone.”

“I really wish you could have met my father,” she said smiling again. “He was a wonderful man.”

Talking to Lila made me feel like I was meeting him.

Bassam and I look at the time and realize we need to hit the road to our next stop in Minnesota. Lila smiles again and asks me to sign the mosque’s guestbook before I leave.

“I will never forget this place and the contributions you, your family and friends have made,” I write. “And I hope nobody ever does.”