By Bassam Tariq

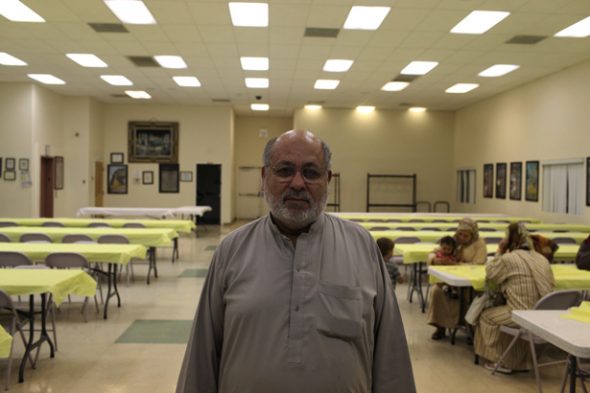

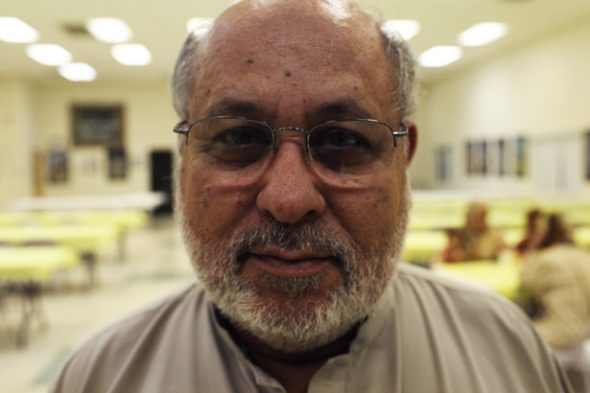

Amanullah has been working in casinos for over 29 years.

“Nobody enjoys this work,” he tells me as he sips on a cup of chai. “But we do it because we want a better life for our kids.”

Amanullah oversees slot machines at the MGM Grand Casino and is a board member of the Jamia Masjid, a mosque in downtown Las Vegas just minutes away from The Strip, the city’s infamous road of casinos and hotels.

Gambling is prohibited in Islam, but Muslims working in casinos is somewhat common here.

Amanullah smiles with an almost cotton-like beard as he talks about the spiritually grueling lifestyle he lives, so that he can make a better life for his kids. He’s an active person at the mosque and I can only imagine the type of criticism he gets from his fellow Muslims for working in casinos.

“They may not say it to me directly, but oftentimes I can feel it,” he said as he nods his head and blinks slowly.

He grew up in Afghanistan and came to the United States in the 1980s when the Soviet Union invaded. He settled in Las Vegas because he had an uncle that lived there that was all alone. He took a casino job because he desperately needed money to support his family and send home to relatives oversees.

“I had no money,” he said. “I used to walk my daughter to school and I would have no money to even buy her milk. I was only making enough to cover rent.”

Many of the people who work in casinos are immigrants from foreign countries like Bosnia, Afghanistan, Morocco, the Philippines and Somalia. Most of them came to Las Vegas because they had friends or family already living here.

Amanullah says he’s never enjoyed working in casinos and it eats at him inside working at institutions that center on indulgence and extravagance.

“In all my years I’ve never gambled or sipped a drop of alcohol,” he said. “I’ve never enjoyed seeing any of this around me and as I get older it becomes more and more difficult to stand this. The only thing that gives me peace is my family and the masjid.”

I stared into Amanullah’s eyes and began thinking about my father. My father travelled 5-6 days a week on the road for a baking company and never enjoyed a single moment of it. But like Amanullah, he did it for his kids. The bags under Amanullah’s eyes remind me of my dad’s as he came home from a long week of work too exhausted to do anything but collapse on the couch.

There’s something many people don’t understand about the need for a man to provide for his family on his own, and what lengths he’s willing to go to in order to make that happen. Amanullah tells me he’d rather do this than rely on welfare or other forms of governmental assistance to feed himself. As much as he hates working in casinos, it helped put his daughter through college.

I spoke with several Muslims at the Jamia mosque who work in casinos. Each of them have their own stories about how they got into the business but none of them enjoy it.

“Look, this life is pathetic,” said Bilal, who recently got laid off from a casino. “The management has so much control over you that you can’t do anything. You can’t even move around without someone watching you.”

I asked him why go through the torment then?

“The money,” he said. “A manager can make somewhere around $85,000. But you’re like a robot at work and all you can think about is your family.”

Bassam and I walked through the Aria Casino on The Strip that many Muslims are starting to work at since it opened in December. I walk past countless rows of slot machines as my ears begin to rattle from the clanging slots that gulp up coins like a vacuum cleaner. My stomach begins to churn as I’m smothered by the smell of cheap cigars and Axe Body spray from tourists trying their luck against the casino card dealers.

I think to myself, “This is the life these Muslims deal with every day, so that their family doesn’t have to.”

As we’re getting to leave the Aria casino, Bassam and I speak with Kariuki (pronounced Karaoke). He’s a Christian man from Kenya who’s been shining shoes in a casino bathroom for three months. He said working here has good days and bad days so we asked him what a good day entails.

“A good day, ha!” he said with a chuckle. “A good day is when I get money. There is no life here. The only thing we do in life is work and sleep. When I go out with someone, all I think about is ‘Is this going to make me late for work?”

Dr. Aslam Abdullah is the director of the Islamic Society of Nevada, the group that runs the mosque and is editor of the Muslim Observer, a publication based in Dearborn, Michigan. Before we left Las Vegas, we chatted about this whole Muslims in casinos issue and the complications surrounding it. He said before we point fingers at Muslims for working in casinos, we really should point fingers at ourselves.

“This is the failure of our leadership and institutions to provide for the social and economic well being of our community,” he said. “I talk about this in the khutbahs (Friday sermons) a lot and I tell people ‘Before you look down on them, find them an alternative.’”

He explained most of the Muslims who work in casinos are immigrants who take the jobs because it’s unskilled labor that pays well. It’s our failure as Muslims, he says, to help them integrate into society and help them find a way of life that doesn’t go against Islamic guidelines. Rather than condemn them and reject them, it’s our obligation as Muslims to help them.

“We’ve developed this ‘holier than thou’ attitude where we look down on people who don’t memorize as many surahs (chapters) of Qur’an as us,” he said. “But what good is memorizing 30 surahs compared to 10 surahs, if you don’t understand or follow any of it?”

Make no bones about it, no Muslim in their right mind will condone the concept of working at a casino. It’s tough to make it in this country, and many of these Muslims will go through morally compromising situations if it means that their children can live a life where they won’t have to. Simply slamming Muslims who works in casinos is too easy and basically pours gasoline on the flames that burn the bridges between us.