By Aman Ali

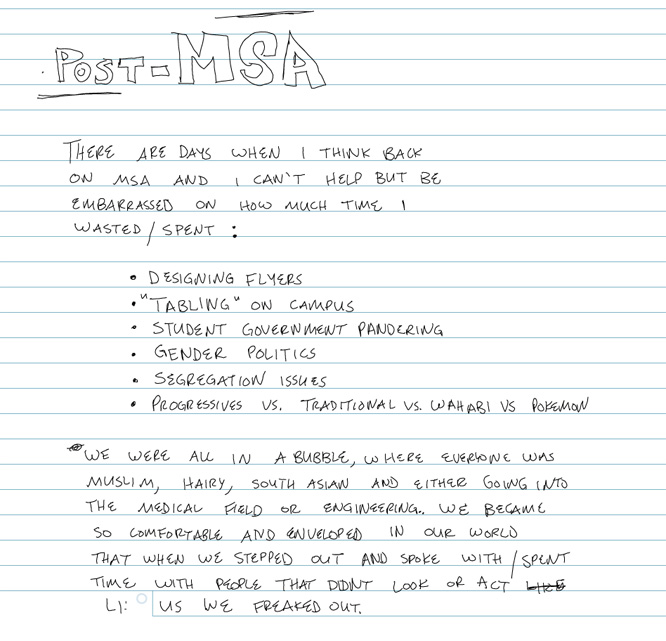

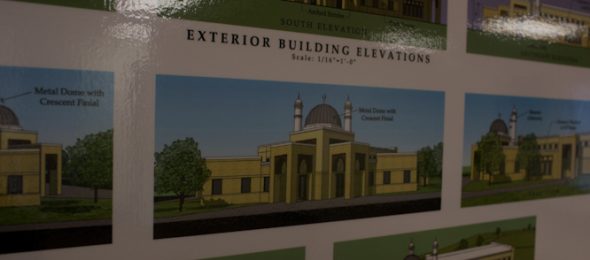

Welcome to Murfreesboro, Tennessee. You may have read about it or seen the CNN documentary about how a fringe group of local residents are trying to derail plans for building a mosque here. The construction site for the mosque has even been subject to arson and vandalism.

I was more interested though in finding out what was happening behind the scenes for the Muslims here. What’s it like to go from living in a small town in Tennessee to getting microphones and news cameras shoved in your face day in and day out?

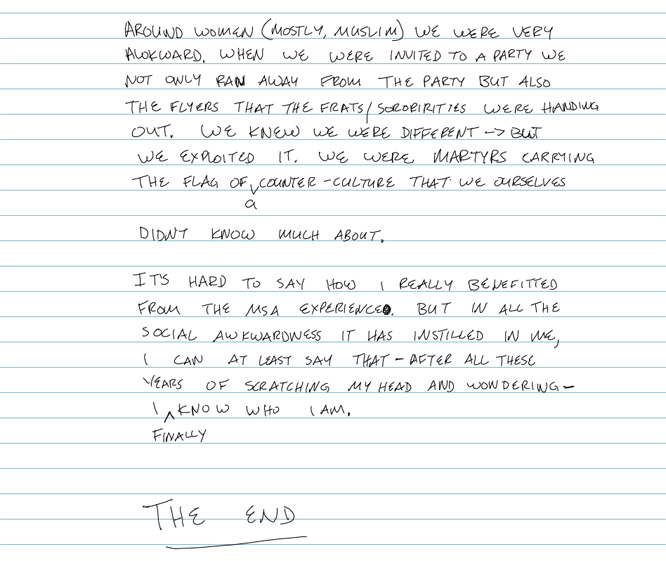

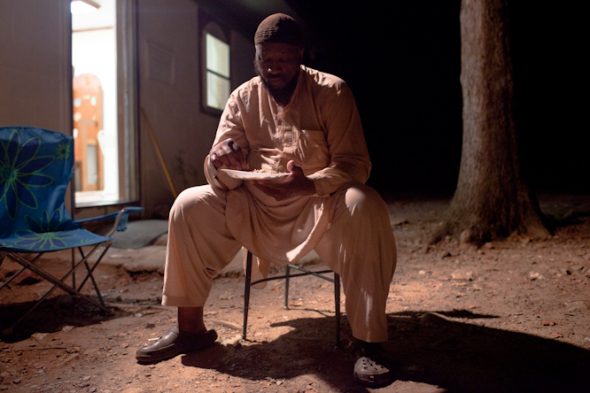

I met the mosque’s imam, Sheikh Ossama Bahloul, in his office to chat about the whole ordeal. He speaks with a dense Egyptian accent pronouncing words like “the” as “ze” or any word with the letter “P” in it as “B.” But he cuts through the language barrier with his intellect. He said he’s well aware the opposition against the mosque isn’t necessarily an anti-Islam movement, but rather politicians stoking flames of fear to score some political points.

“They use the Muslim community in specific areas of the country as a tool in their hand to make specific achievements,” he said. “This is a strategy because of the White House election coming. 27 bercent of the American people believe the president is a Muslim, still! It’s craziness, yaani.”

When the controversy first erupted last year in Murfreesboro, Sheikh Ossama said nobody in the Muslim community anticipated how many news networks would come flooding in.

“The issue became too big,” he said. “The Jabanese TV, France TV, Australia TV came here. What is this, for what? In a way it’s ridiculous.”

I asked him if he did any interviews with Fox News.

“No,” he said before wagging his finger. “Audhu billahi minashaytan nirrajeem (Arabic for ‘Allah, I seek refuge and your protection from the devil’).”

The sheikh had me cracking up constantly with deadpan wisecracks like this throughout the entire interview. Hang out with him long enough and you’ll find out how much of an endearing goofball he is. A photographer was there that day asking us to pose seriously for the camera and I had to keep asking the sheikh to stop making Bassam and I laugh.

“Now this guy, he is looking scary,” Sheikh Ossama said while pointing to Bassam, who was sporting his Blue Steel pose for the camera. “Why you so scary? Don’t do that, I can get scared very easily.”

Sheikh Ossama said he mostly stuck doing interviews for CNN and the BBC. He chose not to do any interview with Al-Jazeera or similar Middle Eastern networks.

“We decided not to go to Al Jazeera or any of the Arabic channels because they would make it a big deal and make America look ugly,” he said. “It’s good to care about the country. American people are nice people. It’s not fair to say they are bad. I don’t want anyone to hate anyone. We must push for love and peaceful activity.”

This isn’t my first time meeting the sheikh. In September 2010, ABC News invited him and I along with a bunch of other people to participate in a Town Hall special on Islam. I chose not to say anything during the special because it turned into a theatrical shoutfest. If you saw the special, you saw the imam constantly trying to jump in and respond to all the ignorant things said during the taping. He told me early on, he often got heated in media tapings like these because it was tough to not respond to all the ignorance he was hearing.

“I couldn’t take it well in the beginning,” he said. “It was difficult for people to call me and give our Prophet Muhammad (peace be upon him) a bad name. It was tough to hear people say we can’t have a Muslim cemetery here in Murfreesboro because it will contaminate the water.”

But soon, he and other people in the community’s irritation to all the ignorance faded.

“People can be angry, but I intend to look at it from this perspective: I believe strongly that Allah chooses people for specific jobs. I believe that Allah chose us for this specific challenge. So in a way I felt Allah gave us an honor to deal with this challenge.”

“When people gave us fake allegations and lies, we were so comfortable because I don’t think it’s proper to make enemies because our life is too short and it’s not worth it. I might get mad here and there, but it’s not a big bercentage at the time because it’s not worth it.”

The Muslims here pray inside an office space inside a shopping center as they prepare to break ground on their mosque project in the coming weeks. I broke my fast in the evening alongside Salim Sbenaty. He’s 14 years old and I remember seeing him on CBS News last year about how he was actively standing up for the mosque and engaging the opposition.

“I’m huge on human rights,” he said. “That’s mainly what inspired me. It’s not more of my own religion that inspired me. If it was any religion, I’d act upon it because everyone deserves these rights.”

“Now how many times have you said that soundbyte in front of a camera?” I teased him.

Like me, Salim has done his own fair share of media interviews so we started riffing about all the silly questions reporters often ask us.

I get the question ‘How do you feeeeeel?????’ about a million times, he said. “Get it from the last guy, do you really have to ask me?”

But he doesn’t get annoyed by it, he added.

“I know that these questions may bring somebody towards better understanding what’s happening,” he said. “Even if I’ve said something over and over and over, it’s for another person that may have not heard it before.

He said he wasn’t prepared to handle all the media attention initially but there was a particular interview where he realized how big this whole Murfreesboro controversy really was.

“I think it was the one I did for Nickelodeon,” he said. “It was that interview when I realized, ‘Wow this is actually an international issue – Murfreesboro, Tennessee.’”

“Wow, Nickelodeon. You were interviewed by CBS News but the network that created Spongebob Squarepants, that’s what did it for you?” I riffed back.

When you’re doing so many interviews encouraging people to better understand Muslims, it’s easy initially to become infatuated with the aura of being on television. I asked him what he does to curb that.

“I try to remind myself that this is my civil duty,” he said. “It’s nothing special. I’m doing this for Allah and only Allah. This isn’t a priviledge or something that I chose to do. It’s my duty of sort.”

Now the “celebrity” in this community I wanted to meet was his older sister, Lema Sbenaty. She was on the CNN special and there’s footage of her grilling this lady running for office bashing the mosque project. Before coming here, I was in touch with her via Facebook where she kept calling me “Mr. Ali,” making me feel like I’m 26 going on 65. I was told she was outside, so I laced up my Puma sneakers and stepped out of the mosque to find her.

“Are you Mr. Ali?” she said pointing to me.

“Dude, I told you not to call me that!” I said. “Makin me feel like an old fart, jeez.”

“Well I dunno, I just saw the bald head and figured it was you,” she quipped.

After seeing her on CNN and learning about her courageous story, I had some burning questions for her.

“The most important question I have for you is, after the documentary aired… how many random people messaged you on Facebook with marriage proposals?” I asked.

She said she’s gotten more than 20! That’s almost twice what I’m getting.

“One guy from Tunisia said ‘I saw your interview and would like to meet your family,’” Lema replied while laughing incredulously. “I was on TV for 25 seconds. Who watches something that makes them want to go on the computer and send a proposal?”

She also gets several messages and emails from Muslim women thanking her what she’s doing. The challenge for Lema was learning to embrace the unwanted role of being a female Muslim role model.

“I don’t want to represent Islam in a bad way,” she said. “It was a big struggle, this whole idea of ‘Am I going to be good enough for these girls to look up to me?’ After the CNN interview, the sheikh came up to me and said ‘You have to pay attention to yourself now because people know who you are. So it’s good in some ways because you remain grounded and in check.”

A fringe but vocal group of people are pumping thousands of dollars into stopping this mosque from being built. As a result, the Muslims become victims of these people’s selfish attempts to exploit them for political gain. But I’m taken back by the relentless strength this community has. I asked the imam where their perseverance comes from.

“It’s good for the human being to recognize the limits in his or her ability,” he said. “I realize this situation is in Allah’s hands. I sometimes say ‘God, I don’t know much and I don’t know how to handle this, please help me’ and God will give you the help you need. If you are arrogant and say you can handle this on your own, you will not do as good.”

“Sometimes what people say can make me angry,” he added. “I’m not an angel. When I hear children in school being called terrorists and little girls coming to me saying they’re too scared to wear the headscarf, it hurts me and makes me angry. But it’s only for a few minutes. Allah chooses people to deal with specific challenges so we are grateful.”