By Bassam Tariq

Understated moments. There are many. Here’s hoping you enjoy one or two of them.

Jesus Fliers

Tired and starting to feel a little hungry, we arrive in Santa Ana, California and began our search for this hidden Cambodian mosque. A large group of people are gathered near the mosque and are passing out fliers. They see Aman and I walking towards them and stop us.

“Hey brother,” one of the older man says.

I smile.

“We have this live concert tonight and would love it if you can come with us. There will be prayer and we’ll be celebrating Jesus.”

I take a flier from him, read it and tell him I’ll think about it.

A block over, I see an open courtyard and three Cambodian women wearing hijab sitting under a tree. Two young girls playing basketball, and a group of young guys hanging out in izaars. Looks like today is going to be an interesting day, I’ll have to take a rain check on that concert.

Two Shots and a News Special

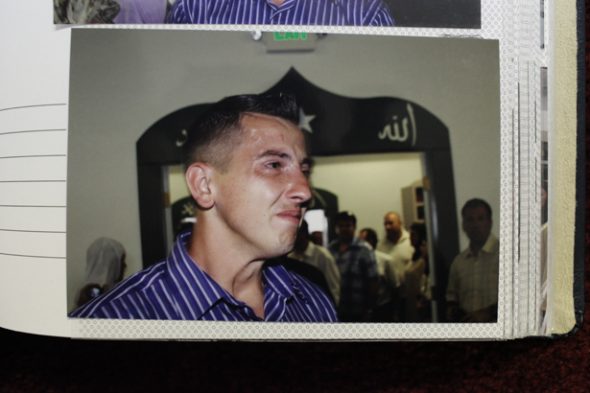

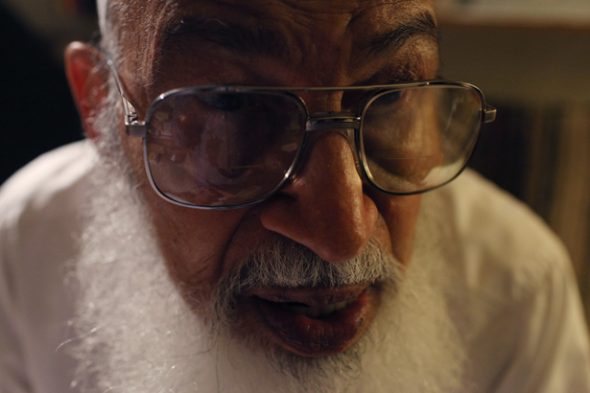

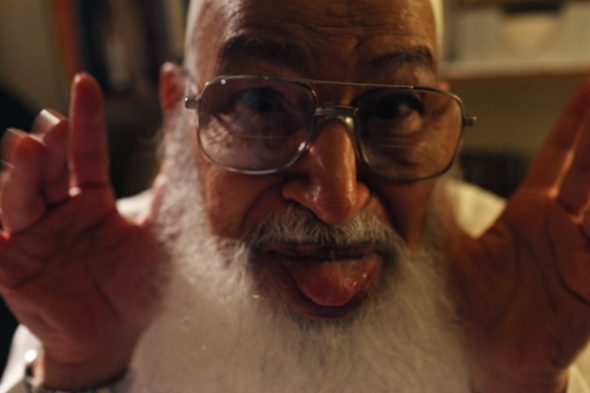

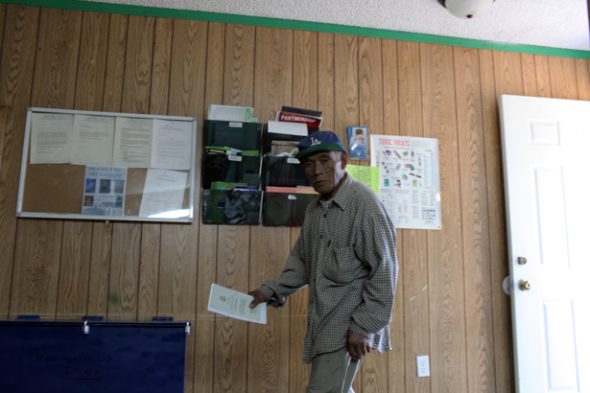

Saleh does what he wants, when he wants. This was made clear when he walked into the masjid, interrupting the conversation we were having with one of the elders in the community, and began grilling us with questions.

“So are you here to raise money?” he asked us.

Aman was quick to clear our name and plug our site. But at that point Saleh was disinterested and continued on his merry way.

He allowed me to take photos of him and looked at each photo after they were taken.

“I’ve been shot five times and I just got out of jail.”

No joke. One of the community members was there when he got shot twice. The story goes something like this – Saleh’s home boy was being picked on by the rival Latin gang and Saleh didn’t like that. He confronted the crew alone and began throbbing punches at six to seven of them. Saleh was uncontrollable, knocking the Latin gang members like bowling pins. They couldn’t stop this Cambodian juggernaut until a guy pulled out a pistol and shot him twice. bam bam and Saleh was on the ground.

Saleh was shot in the butt and leg. The ambulance and local new stations showed up in minutes. As the local news channel reported the shooting, Saleh waved and smiled at the camera as he was being transported into the ambulance. Getting shot in the buttocks and still cheesing for the camera? Yes, that is badassery.

That’s Brisk, Baby

Around the corner of the mosque, a kid walks around with a 20 oz. bottle of liquid.

“This is pee pee.” The kids tell me. He has a thick Spanish accent and smells his plastic bottle with amusement. It looks more like iced-tea to me.

“It’s not piss,” his friend says.

“Smell it!” he yells.

After his friend smells it, the boy runs to me and makes me smell it. And yes, it is pee pee.

The question became less on if it’s pee-pee now and more on who urinated in that bottle?

“Dont look at me…” the kid with the unzipped pants holding the smelly bottle of piss says.

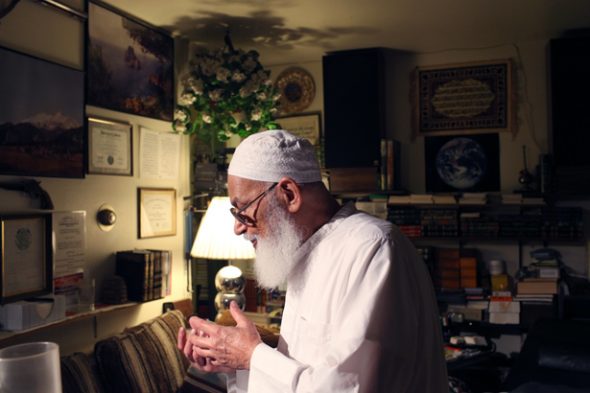

Doctor Who

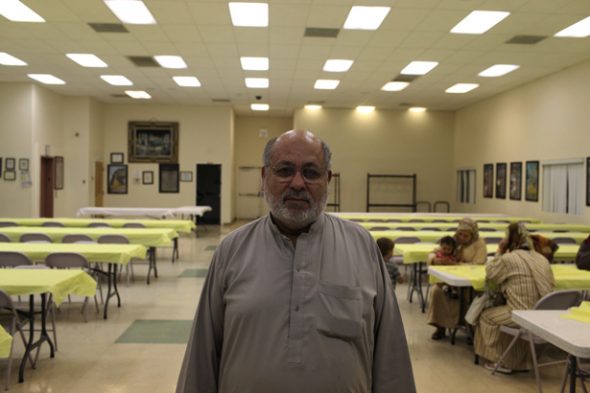

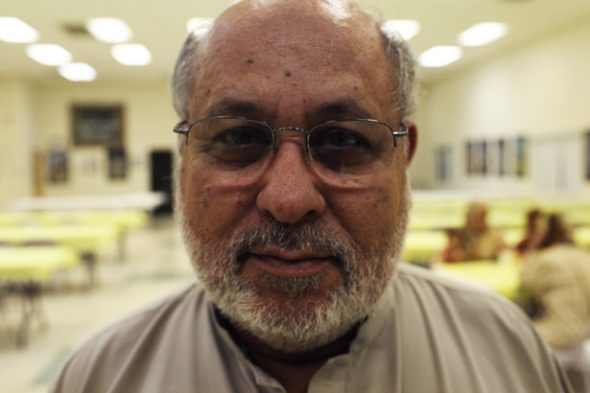

Right after Asr, the afternoon prayer, I sit around in the prayer room with some of the congregants. Their topic of discussion today: expansion.

Like every mosque we have visited in our trip, there were a lot of talks of expansion. The congregation looked small to me, and I wondered, do they really need to expand?

“We need more parking here. There is absolutely no place for parking.” Says Mohammad Saeed, the president of the Mosque. “that is why less people are coming to the mosque.”

Are there more Cambodians that come here for prayer?

“There are more than Cambodians that we have to look out for.”

So what’s keeping you all from expansion?

“I don’t think there is anyone in our mosque that makes more than 15 per hour,” Ghazali, a young man with a bluetooth headset that seemed conjoined to his ear, says, “there are no doctor’s here.”

The congregants nod their heads.

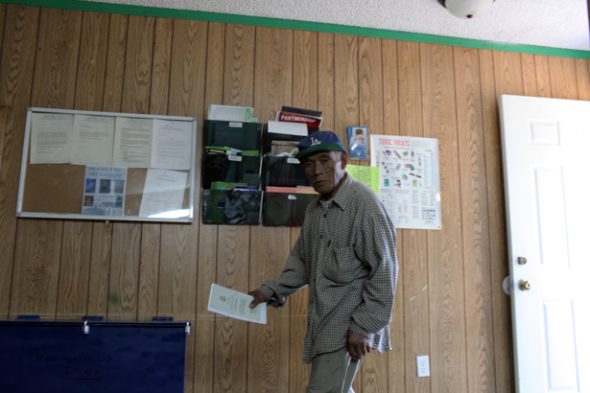

Dodging Shots

I see a man entering the mosque and wait for him to enter so I can take a great candid shot. I begin snapping when he enters. AHHH!! The man screams and flings his back to the camera.

I freak out. Did I do something wrong?

“That is Harun, he is the masjid caretaker,” Mohammad Saeed, the president of the mosque, says, “he was hit by a claymore in Cambodia during the Khmer Rouge. He is not all there. Please excuse him.”

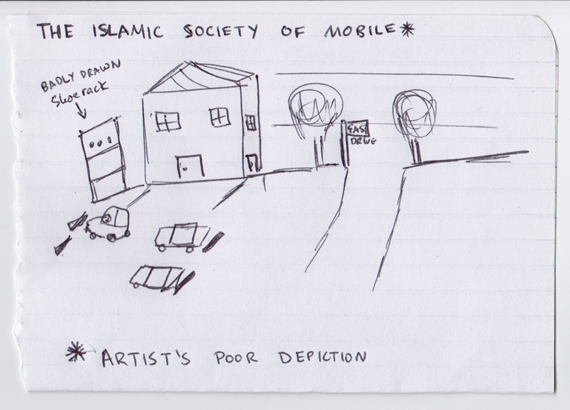

The Grounds

The grounds right outside of the mosque is the center of the community. Two girls from the community play basketball without a goal. The goals break often which ends up making the grounds just an open concrete space.

Abdul Ghoni, I think

Abdul Ghoni halts in the middle of the playground near the mosque and starts doing push-ups. He does five, six, seven and then stands back up as if nothing happened. He is 27 years old and works at the local school. He cleans tables, picks up trash, and sweeps the floors. He tells me what he does with pride and dignity. Kareem, our local guide, tells me that Abdul Ghoni doesn’t miss a single prayer at the mosque.

I ask Abdul Ghoni to spell his for me. He thinks for a minute and asks for a piece of paper and a pen.

I hand him a black papermate pen from my back pocket. He starts shaking the pen furiously because it’s not working. I try scribbling on my hand to see if it works another surface and it doesn’t give in. We leave the pen alone and Abdul Ghoni goes his way. And I stay put speculating how to spell his name.

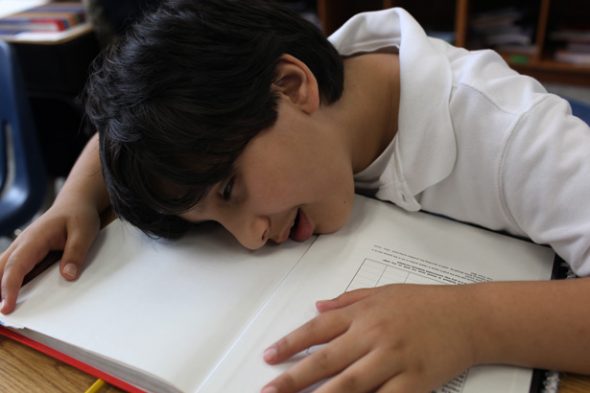

Courts

The basketball goals in the grounds of the mosque are broken all the time, so the kids sneak into the local elementary school to shoot around an hour before Maghrib.

Ayoub’s Truck

I have seen very few parked trucks that sell both funyuns and watermelons. Ayoub, one of the pioneers of the community, runs this truck right outside his house. Ayoub’s wife runs the truck and, surprising, the mobile store helps bring in a decent amount of income for the family. I ask him why he started the truck store.

Ayoub looks over at his wife and says, “Eh, it keeps her busy.”

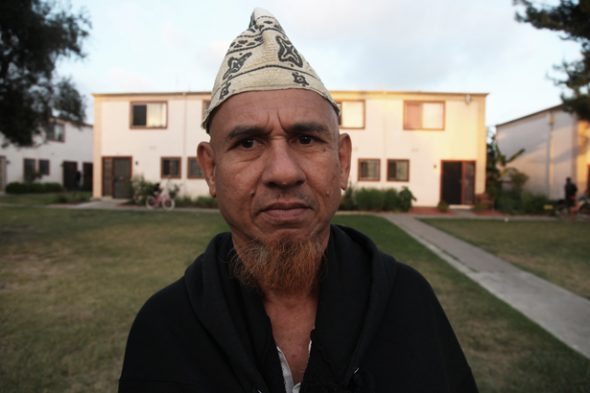

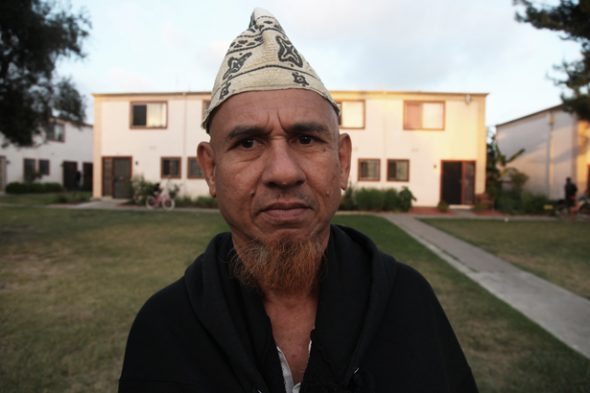

Cambodian Doe

Forgive me, I have forgotten your name. I saw you standing in the distance as the sun was setting in this small neighborhood, where the majority of the congregants are either Cambodian or Hispanic. I couldn’t pass up the opportunity to take this photo.

It took me a while to find the right place for you to stand and then spent the next two minutes snapping away. Thank you for your patience. Also, you have very soft hands.

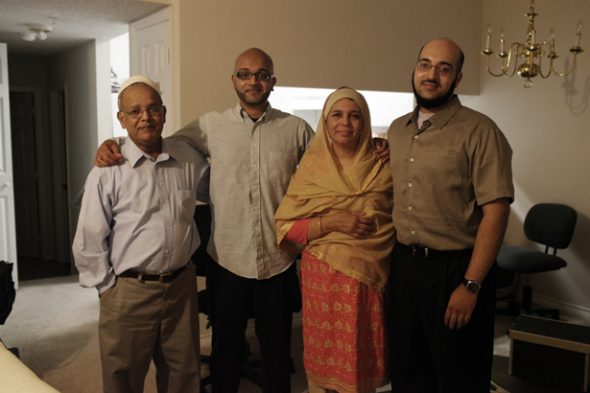

Great great great

Three generations old. She came when she was in her early 60′s. She walks around the community space. She sits under the shade of the tree waiting for her other friends to show up.

“The elders in our community are dying,” Mohammad Saeed, the president of the mosque tells us, “just last year, we lost five elders.”

The great great great grandmother looks over at the sun, patiently waiting for Maghrib, the time for break fast, to approach.

Food Time

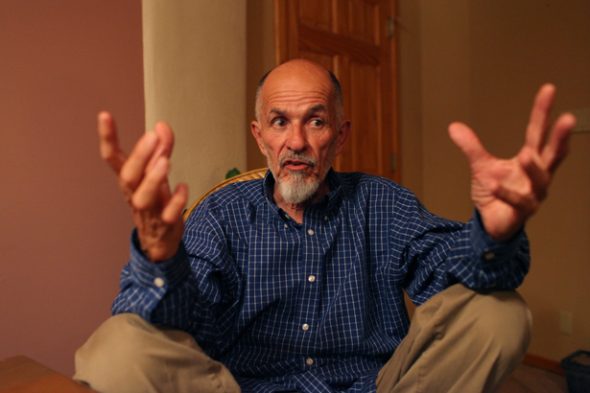

Un-Pakistani

Looking for a place to sit with my dinner plate, I somehow end up next to a group of three Pakistani guys. We all look at each other and ask ourselves, “how did he end up here?”

After telling them about the 30 mosques project, I ask them how they got here.

Malik lives about 20 minutes away from here. There are three other mosques that are closer to him, but goes out of his way to come here.

“There is no politics here. No elitism. There is none of those things that are found at the local Pakistani mosque. Everyone here is unassuming,” Malik says.

“Really?”

“Yeah! In those Pakistani mosques the doctors sit here, the engineers here, and the cab drivers here. Over here, there is none of that. No one will ask you what you do for a living and everyone sits together.”

After Malik said that, I couldn’t help but wonder what he did for a living — it must be Pakistani in me.

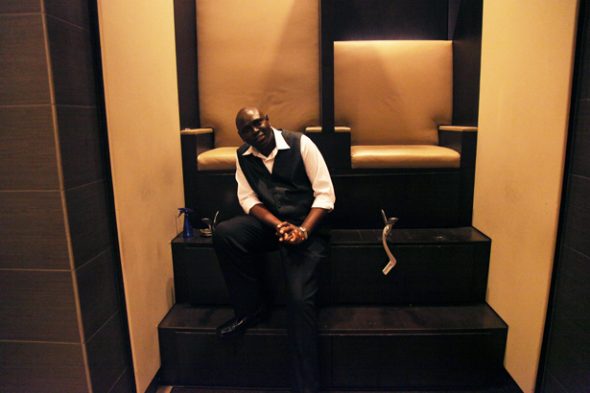

Matt, er, Mohammad Saeed

“I don’t feel like vacuuming,” Mohammad says after we break our fast, “I’ll just do it tomorrow.”

Outside of the community, Mohammad goes by Matt Ly. He is the el jeffe of the center. A stout, but muscular man who watches over the entire mosque operations. He stares at the carpet, picking up small pieces of lint and crumbs of food with his hands.

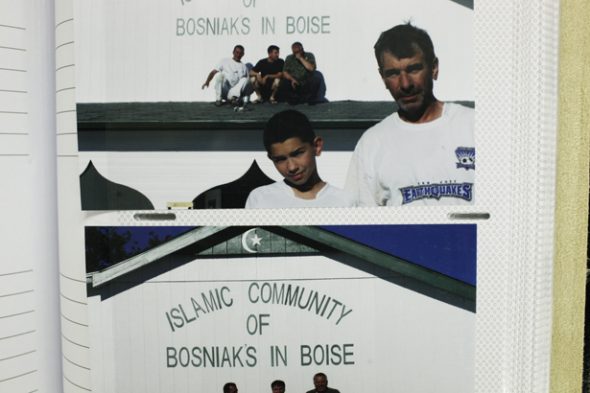

Mohammad’s uncle was one of the first Muslim Cambodian refugees in 1979. He sponsored 17 Cambodian families and brought them to the states. This was considered one of the first emigrations of the Cambodian Muslims to the states. When the families first came from Cambodia they started in different cities and went their own ways. A small community ended up in Santa Ana and established this mosque in 1982. Soon enough, the Santa Ana community began calling all the Cambodian Muslims convincing them to settle here in Santa Ana.

The brutal communist regime, Khmer Rogue, had killed and tortured many in Cambodia. Religion wasn’t allowed, so the Cambodian Muslims would pray secretly and hold small Friday prayer services. They all had an incredibly difficult time and went through it together. So when many of them settled in the States, it made sense for them to live amongst one another and heal together.

Mohammad was 17 when he escaped Cambodia. After things finally calmed down, he went back to Cambodia in hopes of staying, but ended up coming back to the States. His family is here, his work is here.

“When I leave to a different state, I miss California because, you know, it is home.”

Mohammad pauses.

“But when I go back to Cambodia my heart rises and I don’t want to be anywhere else.”

Mohammad gets up, heads towards a closet and comes out with a vacuum.