By Bassam Tariq

Before Break Fast, Reflection

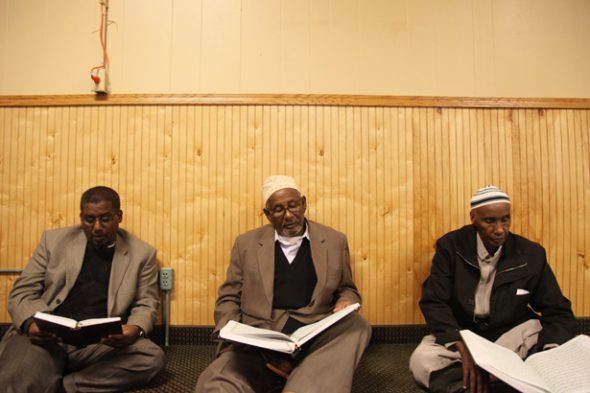

We arrive around 6 PM to Dar Al Hijrah, the local mosque in downtown Minneapolis, and are welcomed by the congregants of the community. A group of elders sit around reciting Qur’an together. They take turns reading the first part of a verse and then everyone recites the last part together. It sounds difficult, but the harmonies are incredible.

Before entering the mosque, I make a point to get permission to shoot photos and video of the community. I speak on the phone with Abdul Qadir, the executive director of the community, and get his permission for taking photos, but told me to be mindful of the congregants as a lot of them are a little weary of people taking photos. People being weary of having photos taken is not unique to the Somalian community, we’ve have been experiencing this since the beginning of the trip. But the level of unrest and uneasiness I felt from the congregation when I took out my camera was new.

Minneapolis is known for its large Somalian community. According to Abdul Qadir, the executive director of Dar ul Hijrah, There are close to 10,000 Somalians in the twin cities. They began to come when the Civil War broke out in Somalia in the 1990s. We’ve found small pockets of Somalians throughout the country, but the community in Minnesota/St. Paul is by far the largest and most well-established.

The Riverside Plaza, a large high-rise apartment complex, is where many of the newly refugees are placed. It is a government subsidized complex that is predominantly East African. Just walking around the street, you will be greeted by women in long flowing abayas and men with kufis. The Somolian community got together and rented a small room in 1998 in a building right next to the housing complex to conduct prayers. In 2006, the entire building came on sale so they decided to buy the entire building. They called this community center Dar Al-Hijrah, the home of Immigrants. Ironically, as the mosque expanded, it also got a next door neighbor, Palmer’s Bar.

I asked Abdul Qadir what the relationship was like with the pub and he said they’ve been very accommodating.

“Sometimes, the music gets a little loud, but we just tell them to kindly put the music down for us to pray. And they are very respectful.”

Regardless of the level of respect, Abdul Qadir acknowledges the awkwardness of the proximity.

Breaking fast, sort of

The congregants break their fast with dates and bread. The mosque only provides food on Saturdays and Sundays. Soon after I devour a date, a member of the mosque performs the call to prayer to get everyone together for maghrib, the sunset prayer.

Afterwards, The Party

After breaking their fast, many Somalians go back to the mosque for taraweeh, the night prayer, or, those that are not working, are out socializing. You will find a large number of Somalian brothers at the International Corner on 15th and Nicollette. You can google it, or just follow the loud clanking sounds of the dominoes. The sound of dominoes hitting the table, the constant yelling back and forth meshed with foozball slammery drowns the place — this coffee shop is bursting with energy.

I start taking photos at the pool table, and then head over to the internet hub. I finally make my way to the rowdiest part of the coffee shop, the guys playing dominoes.

As I take photos of the people playing dominoes, I hear a man screaming from two tables away in my direction. He gets up from his seat, points and yells at me. Suddenly, two men grab him and hold him back. The guys playing foozball at the adjacent table come around and start probing me. A group of men surround me.

“What did you do wrong?” says one of them.

Nothing.

I start handing out our yellow 30 mosques business cards hoping to calm people down by showing that I’m a Muslim and not the government. But no one is buying it.

“Are you the FBI? Did the government bring you here?” A brother says to me in my face.

I should note that most of these men tower over me. If I was in need to head butt any of them, I’d need to stand at least on one or two stools.

“Alright, thats enough.” says a Somalian brother, holding the brother back and saving the day.

I am able to get a couple of more photos before another guy playing dominoes gets out of his seat throws the dominoes on the ground and complains to the owner. Ahmad, the owner, calms him down and tells him to leave if he will continue to be loud.

I’m freaked at this point, but everyone around me has started laughing.

“Did I do something wrong?” I ask the guy who saved me.

“Nah. this is just the way we have fun in Somalia.” he replies laughing.

This guy is Eid Ali. He is a cab driver and sits on a leadership board that speaks with the local government about their issues and concerns. Eid is an eloquent, unassuming man. We move towards the computers and begin to talk. After some convincing, he happily lets me join him on the road for a half an hour. .

“Look, don’t take offense.” Eid says to me as we’re driving. “Ever since people from our community left to fight in Somalia, the FBI and the media has been down our throats.”

I wasn’t sure what he was talking about, but make a mental note to Google it later. (LINK)

Soon enough, Eid parks his taxi and I start to take photos. After about 30 minutes, he looks at his watch.

“Am I keeping you from something?” I ask.

“Well, today is Friday, it is a busy day for us cab drivers.”

We exchange numbers and part ways.

The Next Day

On the road to Milwaukee, I place a call to Abdul Qadir, the executive director of the Dar Al-Hijrah, to ask him a question.

“Why is the name of the mosque Dar Al-Hijrah, ‘the home of immigrants?’” I ask.

Abdul Qadir pauses on the phone.

“I don’t really know. I didn’t attend that meeting when they named the masjid.” He says, “but I think it’s kind of a way to attract people. I mean, we’re all immigrants here and we’re just trying to figure out how to get around.”