By Aman Ali

Brother Ali is just as beautiful on the outside as he is on the inside. When you talk, he listens by nodding in excitement with a nirvana-like smile that stretches across his face. He sports a primped beard that straps down the sides of his face and flows down his chin like a waterfall. I’m looking forward to this conversation because I’ve been a fan of his music for almost a decade and like Pac-Man I gobble up just about every hip-hop record he puts out or interview he does.

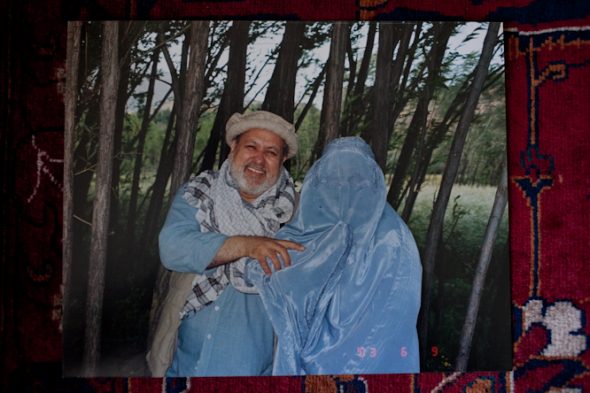

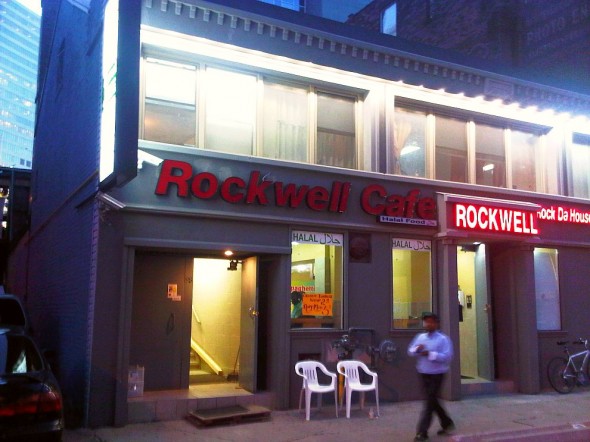

Bassam and I met up with him and his son Faheem in their native Minneapolis for dinner at an Arab restaurant by the mosque we prayed at. I order a few platters for everyone and within minutes our table is toppling with luscious plates of lamb shawarma, beef skewers, roasted chicken and kabobs. Hands start flying in every direction grabbing food as our conversation begins.

“Your son is a beast,” I say to Brother Ali while pointing to how much food his son was eating.

Faheem smiles and grabs a bottle of hot sauce.

“Faheem is ‘The Hot Sauce Man,’” Ali said with a chuckle. “Sometimes for snack he’ll just eat hot sauce and bread.”

“Sometimes at home my mom will have to raise her voice at me because half the bread is gone from all the hot sauce I eat” Faheem said as he puffed his chest.

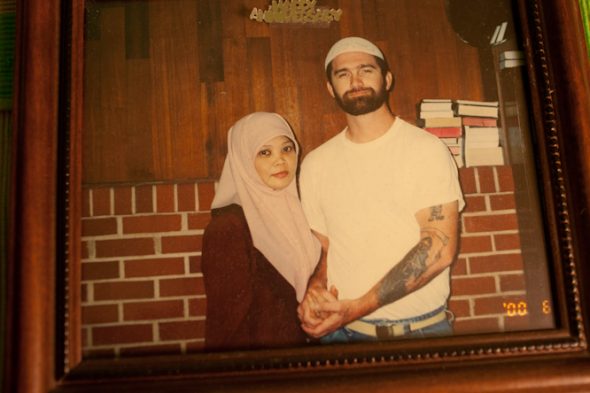

Brother Ali was born with albinism, a genetic disorder that takes away pigment in your skin, hair and eyes. He’s also legally blind. He had trouble fitting in at school because he didn’t think there was anyone he could relate to.

“The schools I went to had mostly white kids in it,” he said. “Then you’d have like one Vietnamese kid and maybe one Indian kid.”

“I was that one Indian kid at my school,” I chimed in.

Being teased about his appearance was tormenting, he said. Until he was seven years old when an African American woman at school told him something that he still remembers to this day.

“She said ‘You look that way because you’re special,’” he said. “’If God wanted you to be like everybody else and just be normal, he would have made you that way. But he made you look special because you’re supposed to be special. If you’re going to be special, all the stuff you’re going through is training for that.’

“And the thing is,” he added. “She didn’t just say it. She made me believe it.”

Intrigued by what she said, Ali began hanging out with the black kids in school and cracking jokes with them.

“I got the same laughs they got when I gave jokes,” he said. The jokes they told me weren’t cruel, they were meant to be funny. That was the first time I ever felt like a human being – when someone called me Santa Claus or Phil Donahue.”

Hanging out with African Americans started his journey on finding his identity which became even more clearer when he became Muslim in the late 90s.

“Islam was just a natural extension of that journey,” he said. “In the sense that you were made exactly the way you’re supposed to be and that God has a plan for you.”

Ali may be white but has said repeatedly in interviews he credits the African American community for raising him. I’ve heard him make that point a lot and was intrigued to find out his reasons why.

“When it comes to the African American experience, no group of people has had to be completely reset in terms of humanity,” he said. “That all has meaning in the plan of God. I’m convinced they’re here to teach us. We have centuries of accumulated stuff. Just this junk that’s been added on to us over time. Not as Muslims but as humans. African Americans are here to live an example of what it means to be a human being again, what it means to be Adam again.”

Ali is on fire right now dropping some serious knowledge on this table and I insist he eat some shawarma in front of him before it gets cold.

“I’m good,” he said while placing his hand on his heart and flashing his radiant smile again. “It’s not polite to talk with your mouth full.”

Brother Ali’s early records focused a lot on his identity struggles and his rocky upbringing. As he started gaining buzz among fans he didn’t expect he’d have, kids from privileged backgrounds that didn’t have even a remotely similar upbringing compared to his.

“All of a sudden, I realized a majority of my fans are privileged people,” he said. “For a couple of years I struggled with trying to figure out why and I realized they might not listen to my content coming from somebody else but they might listen to it from me if I did It right.”

His more recent albums focus heavily on his spirituality, social justice and the connection between the two. Now, times are good for he and Faheem. Ali tours the globe regularly to a steady fanbase and Faheem comes along too whenever he can.

There’s a school of thought out there that says to be a good artist, you have to be dealing with tragedy or torment. Since times are good for Brother Ali, Bassam and I asked him how that impacts his creativity on the mic. He said he turned to the Sufi traditions within Islam to learn there was a whole new world of expression he could explore.

“The Sufi art is what made me know that there is art to be made during times of love,” he said. “They always concentrate on the connection between love and suffering. You can only love as deep as you can suffer.”

I work as a standup comic and I’ve always admired Brother Ali’s stage presence. On stage early on in my career, it’s easy to constantly overthink about everything like “Am I talking too loud?” or “Am I standing to straight?” or “What am I going to say next?” But when I first saw Brother Ali perform at a hiphop show I went to in 2004, I couldn’t help but marvel at how much fun he was having on stage. He was in the zone, dancing on stage and even grabbing the mic to do a quick beatboxing session.

“All that stuff growing up that I’ve always had that nobody cared to see, now all of a sudden I’ve got an hour on stage to give that to you,” he said. “It’s an incredible feeling.”

One of the most difficult things to battle with as a public figure is ego. I have nowhere near the success as Brother Ali does, but it’s a constant struggle to keep yourself in check when people are constantly coming up to you to say they like what you do (or in some female cases they like you period). I asked him how he’s been able to handle his ego battle.

“I wish I could say I’ve been successful at battling it,” he said. “Anybody that’s in front of people, it automatically makes you a narcissist.”

“Dr. Su’ad Abdul Khabeer once said ‘Whenever I go in front of people, I go between feeling inadequate to delusions of grandeur,’ he added. “And that’s so true man. We go from feeling like “Ahhh this is so terrible!” because we’re examining ourselves to ‘I’m brilliant, so brilliant.’”

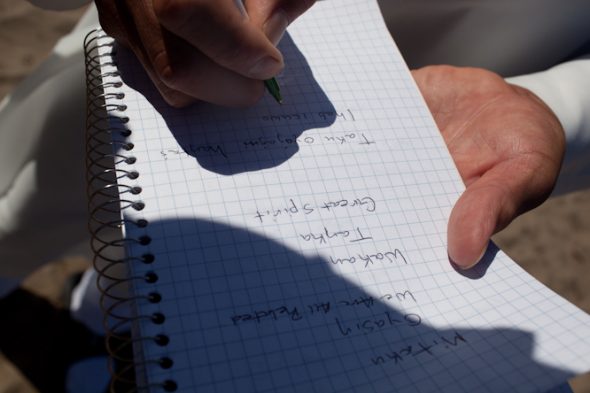

When fans ask for his autograph, he said, one of the things he does to check himself is sign his name with Arabic phrases underneath like “Alhamdulillah” (All praises are for God) or “Allah Akbar” (God is the greatest).

“It’s a double thing for me because it’s reminder to me that you’re signing this autograph because Allah favored you and gave you this opportunity,” he said. “But then when they’re also like ‘Hey dude, what does this mean?’ I say back ‘You’re going to have to find a Muslim and ask them what it means.’”

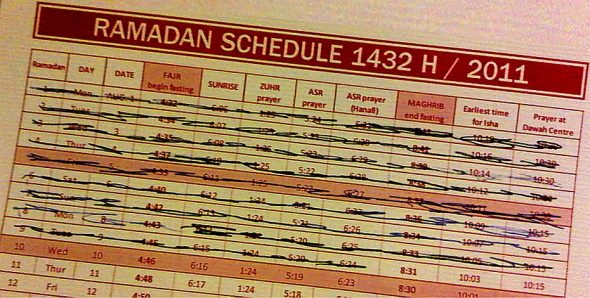

It’s time for the Ramadan Taraweeh prayers at the mosque and Brother Ali wants to leave the restaurant and head over there. I noticed he barely touched his food and carries it outside in a box with his son.

“Dad, I think we should feed this to a homeless person or someone else in need,” Faheem said.

While Ali attends the Taraweeh prayers, I duck out of the mosque and make a quick food run for him with a friend. After the prayer finishes, I hand him and his son a halal Stromboli stuffed with pepperoni, beef sausage, lamb gyro and chicken. Ali bites into it and pauses.

“That’s what’s up,” Ali beams with his smile.

But Ali can only get a few bites in before Faheem devours the entire thing.

“I told you, the kid is a beast.” I said.

I’m going through my notes from my conversation with Ali right now and keep saying to myself “Damn, I didn’t fully realize what he said until rereading it now!” I don’t even think I’ve typed up half of the things we talked about because we covered so much ground over the course in 45 minutes. It’s the exact same thing he does with his music. He orchestrates his insight into the human experience in ways that only he is capable of doing. But I say all this not as a fan nor as an attempt stroke his ego. But rather, as his friend. At first I thought to myself “Ok, we’re friends now because we hung out and I got his phone number.” But then I realized I’ve been connected to him ever since I stumbled upon one of his records over 10 years ago. It’s people like him that helped me embrace my own identity and make sure I feel good about the work I do and make sure it is done to please God most importantly. I don’t know how successful I am on this objective, but I’m blessed to know he has always been here to help me in the process.